Sunday, 9 January 2022

Friday, 7 January 2022

Tuesday, 21 December 2021

could have been a memorial stone to either 'Cnegumus son of Genaius' or 'Genaius son of Cnegumus'.

Evidence of early medieval habitation at Mawgan is in the form of an inscribed pillar stone, located at the meeting of three roads at the center of the village; it bears an inscription that is no longer readable, but based on an old drawing and a photograph taken in 1936 it could have been a memorial stone to either 'Cnegumus son of Genaius' or 'Genaius son of Cnegumus'. The date of this inscription is not certain beyond having been carved before the twelfth century.

At Trelowarren is the estate of the Vyvyan family who have owned it since 1427. The Halliggye Fogou at Trelowarren is the largest in Cornwall. Trelowarren House has a complex building history: the original house is mid 15th century and there are later parts dated 1662, 1698 and ca. 1750 (further additions were made during the 19th century).

Thursday, 16 December 2021

damnonia healthy: 'Sars-like' coronavirus

Sunday, 12 December 2021

Tuesday, 23 November 2021

Vikings were active in Devon

Bloody Pool

Tim Sandles March 25, 2016 Tales Of Dartmoor 1 Comment 5,976 Views

On the south eastern edge of Dartmoor is a rather unspectacular pool known as ‘The Bloody Pool’. It is rumoured that this was once the site of a furious battle between a marauding band of Viking warriors and the local army. Many a brave soul lost his life that day in the shield wall and many were wounded. For hours the two mighty armies stood shield to shield, hacking and slashing at each other. Eventually the invaders were forced to flee back to their longships and return to the sea. The mighty dragon of the Norsemen had been sent home in disgrace but this was no consolation to the widows and fatherless children left weeping at their losses.

To this day it is said that the ghostly sounds of battle can be heard coming from the pool. At certain times, tradition has it that the marshy pool turns red, this is from the blood of the slain warriors who lie buried beneath its still waters. In 1854 a hoard of what were thought to be bronze spears were found near to the pool, it was first thought that these were spears used in the battle but then early archaeologists indicated that they were Bronze Age fishing spears.

If we first start with the belief that there was a battle between local warriors and marauding Norsemen – this cannot be confirmed. However it is a known fact that for many years the Vikings were active in Devon with attacks and raids all around the coasts and inland at Exeter, Tavistock, Lydford. Totnes lies about 6 miles to the south-east of Bloody Pool and was one of the four Devonshire Saxon burghs. which lies about 10 miles south-east of Bloody Pool. The Anglo Saxon Chronicle, Swanton, 2003 p.65, records that in the year 850:

“Here Ealdorman Ceorl with Devonshire fought against the heathen men at Wicga’s stronghold and made a great slaughter there and took the victory.”

The footnote on page 64 tentatively suggests that although the place has not been identified, Wicga’s Stronghold or Wicganbeorg could be modern day Wigborough in south Somerset. Gore 2001 p.35-6 on the other hand states that Wicganbeorg is possibly now a small hamlet called Weekaborough which lies about 10 miles east of Bloody Pool. Glover, Mawer and Stenton in their definitive book, Place Names of Devon, p. 506, are non-committal as to whether Weekaborough was Wicganbeorg because they note that in the transformed 1827 version of the place name, i.e. Wickaborough, the vowel development needed to change the voiced cg to the unvoiced k would be difficult though not impossible. But it still could be possible that there was a battle or skirmish at Bloody Pool If Weekaborough was the Wicganbeorg mentioned in the Anglo Saxon Chronicle.

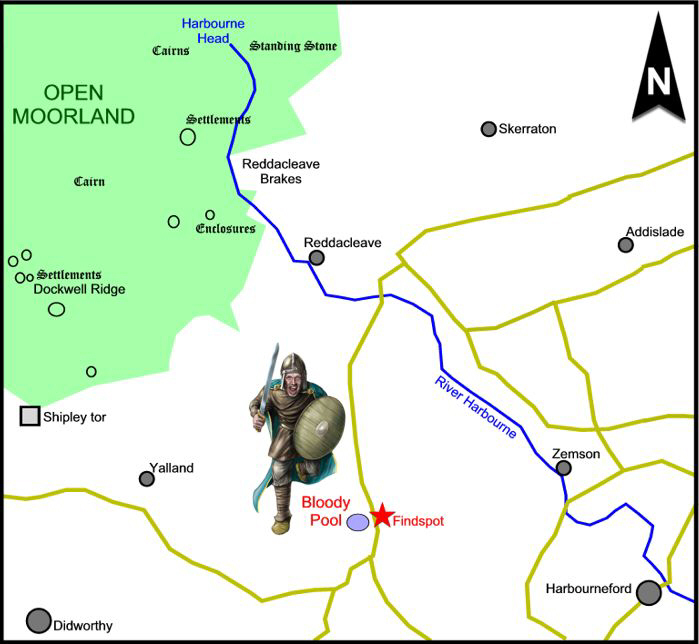

As to the story that in time of flood the water runs red from the spilt blood of the warriors, clearly that is a nonsense but as always there is a possible reason for the strange occurrence. This time it is necessary to look at place names and also local geology. As can be seen from the map below there are two places above bloody pool called Reddacleave and Reddacleave Brakes.

There are many place names on Dartmoor with the descriptive element red and when applied to streams or brooks it usually indicates that the stream bed literally is of a red hue. This is due to the presence of limonite and Hemery, 1983, p.58, describes it as being “a reddish substance of paste-like consistency that clings to stones in the peat-bog stream-beds in their upper reaches, during periods of drought when the water is low and the current sluggish. It results from the oxidation of ferrous carbonate, a derivative of the bog.” Could it possibly be that the reason the pool turns red is due to the limonite giving the water a red hue as it does elsewhere on the moor?

With regards to the hoard of Bronze Age fishing spears, this is a fact and they were discovered in 1854, a fact first noted in Crossing’s book ‘The Ancient Stone Crosses of Dartmoor, p.10. He also notes that they could be seen at the Albert Memorial Museum in Exeter. Today the findspot is recorded as being SX 7029 6263 and they are classified as being “four bronze spearheads and ferrules, each broken in three places”. They have been dated to the Bronze Age and carry an ID Record of NMR SX 76 SW 14, described as consisting of “four bronze ferrules, 7″ long found with four barbed bronze spearheads which are 14″ long, all but one was broken. suggested as a Merchant’s or Founder’s hoard.”

Adapted from Pearce, 1981, p.127.

The map above clearly shows many Bronze Age features such as Enclosures, settlements, cairns and a standing stone so therefore it is no surprise to have discovered a Bronze Age hoard. What is interesting is that it should have been discovered by a pool, according to the NMR report they are considered to have belonged to a founder’s or merchant’s hoard but was this in fact a votive offering of some kind? Pearce, 1978, p.76, remarks that:

“… spearheads like this form a well-recognised type and are often found as groups or hoards in contexts which suggest they were ritual offerings. The Bloody Pool spearheads may have been thrown into water, and everything we know about the late prehistoric religion suggests that this was a characteristic method of dedicating offerings to the gods.”

Hundreds of votive offerings have been found in Britain and many of them have been deliberately placed in water. Another similarity that most show is that they have been deliberately broken. Parker-Pearson notes that this act of deposition and destruction at Flag Fen was as if the site was being used as a “wishing well on a very grand scale, 2005, p.109.

There may be no connection but as can be seen on the above map, there is a standing stone near the source of the river Harbourne which is just upstream from Bloody Pool. None of the other identified standing stones on Dartmoor are sited so close to a head spring as this standing stone, known as Harbourne Man. Could it possibly be that sometime during the Bronze Age the main cult of worship in this area was one concerned with water?

Glover, J.E.B, Mawer, A. & Stenton, F.M. 1998 The Place Names of Devon, English Place Name Society, Nottingham.

Gore, D. 2001 The Vikings and Devon, Mint Press, Exeter.

Hemery, E. 1983 High Dartmoor, Hale, London.

Parker Pearson, M. 2005 Bronze Age Britain, Batsford, London.

Pearce, S. M. 1981 The Archaeology of South West Britain, Collins, London.

Pearce, S. M. 1978 Devon in Prehistory, Exeter City Museums, Torquay.

Swanson, M. 2003 The Anglo Saxon Chronicles, Phoenix Press London.

Friday, 29 October 2021

Stoke Mandeville: Roman sculptures

Stoke Mandeville: Roman sculptures HS2 find astounding, expert says

- Publishe

IMAGE SOURCE,HS2/PA MEDIA

IMAGE SOURCE,HS2/PA MEDIAArchaeologists have uncovered an "astounding" set of Roman sculptures on the HS2 rail link route.

Two complete sculptures of what appear to be a man and a woman, plus the head of a child, were found at an abandoned medieval church in Buckinghamshire.

The discoveries at the old St Mary's Church in Stoke Mandeville have been sent for specialist analysis.

Dr Rachel Wood, lead archaeologist for HS2 contractor Fusion JV, said they were "really rare finds in the UK".

"To find one stone head or one set of shoulders would be really astonishing, but we have two complete heads and shoulders as well as a third head as well," said Dr Wood.

"They're even more significant to us archaeologically, because they've actually helped change our understanding of the site here before the medieval church was built."

IMAGE SOURCE,HS2/PA MEDIA

IMAGE SOURCE,HS2/PA MEDIA IMAGE SOURCE,HS2/PA MEDIA

IMAGE SOURCE,HS2/PA MEDIAA hexagonal glass Roman jug was also uncovered with large pieces still intact, despite being in the ground for what is thought to be more than 1,000 years.

Dr Wood added: "They are so significant and so remarkable that we would certainly hope that they will end up on display for the local community to see."

Archaeologists have been working on the site and about 3,000 bodies have been removed from the church, which dates back to 1080, and will be reburied elsewhere.

Since work began in 2018, the well-preserved walls and structural features of the church have been revealed, along with unusual stone carvings and medieval graffiti including markings believed to be sun dials or witching marks.

It is believed that the location was used as a Roman mausoleum before the Norman church was built.

The village was originally recorded as Stoches i

Stoke Mandeville was also the location of the Stoke Mandeville Games, which first took place in 1948 thanks to doctor Ludwig Guttmann and are now known as the IWAS World Games. The Games, which were held eight times at Stoke Mandeville, were the inspiration for the first Paralympic Games, also called The Stoke Mandeville Games, which were organised in Rome in 1960. The wheelchair aspects of the 1984 Paralympics were also held in the village. The London 2012 Summer Paralympics mascot, Mandeville, was named after the village due to its legacy with the Games. Stoke Mandeville Stadium was developed alongside the hospital and is the National Centre for Disability Sport in the United Kingdom, enhancing the hospital as a world centre for paraplegics and spinal injuries.

On 13 May 2000, the new Stoke Mandeville Millennium village sign[3] was unveiled. It stands on a small brick plinth on the green outside the primary school. The sign shows colourful images on both sides of aspects of village life over the centuries.

In 2018 in preparation for the construction of the HS2 high-speed railway, archaeological excavations began on the site of the old St Mary the Virgin church,[4] As well as excavating the church the process involves moving the remains of those buried in the churchyard.[4] which dates back to 1080. In September 2021, archaeologists from LP-Archaeology, led by Rachel Wood, announced the discovery of remains on the site of the church. They had unearthed flint walls forming a square structure, enclosed by a circular borderline and burials.

Monday, 5 July 2021

Dyfed Archaeological Trust

Archaeologists have discovered the human remains of around 200 people, believed to belong to a Christian community going back to the 6th century at a popular beach in Pembrokeshire.

The remains at the foot of the dunes in Pembrokeshire’s Whitesands Bay, to the west of St. David’s, will be stored at the National Museum of Wales.

A team from Dyfed Archaeological Trust and the University of Sheffield are studying other secrets the dunes hold before they are lost to natural erosion and storms.

Archaeologists have been interested in this area for several decades since the early 1920s. So far, teams have exposed almost 100 graves following two excavations in 2015 and 2016.

Gallery: Pirate loot and other treasures found underwater (Lovemoney)

1 of 35 Photos in Gallery©Look At That Booty/Wikimedia Commons

Sunken treasures, shipwrecks and more

The Dyfed Archaeological Trust said there is “still a significant amount of evidence left to excavate,” including an “intriguing stone structure which pre-dates the burials”.

Detailed analysis by the University of Sheffield indicate that the burials included a mix of men, women, and children. The bodies were aligned with the head pointing west and without possessions, in keeping with early Christian burial traditions.

Jenna Smith at Dyfed Archaeological Trust, leading the excavation, said the preservation of the bones is “absolutely incredible” because they have been completely submerged in sand.

“It’s really important that we do so because it gives that snapshot in time which we don’t normally get in Wales,” Smith told the BBC.

“The bone doesn’t normally exist, and the main reason that we’re here is because we are here to stop the bones and the burials from eroding into the sea.”

The site will be refilled after excavation ends on July 16.