YELVERTON

Yelverton or Elford-town—Longstone The Elfords "The Silly Doe"—Mr. Collier on otter-hunting—Sheeps Tor church—The reservoir—The old vicarage—The Bull-ring—Rajah Brooke—Roman's Cross—The Deancombe valley—Coaches—Down Torstone row—Nun's Cross—Roundy Farm—Clakeywell Pool—Strange voices—Leather Tor—Drizzlecombe and its remains—Old customs at Sheeps Tor—Meavy—Church—Marchant's Cross—China-clay and William Cookworthy—The Dewerstone—The Wild Huntsman—Tavistock.

YELVERTON is a corruption of Elford-town. The mansion near the station was formerly a seat of the Elfords of Sheeps Tor. The family is now extinct, at least in the neighbourhood where at one time it was of dignity and well estated. Yelverton is itself a mere collection of villa residences of Plymouth men of business, but it forms a convenient point of departure for many interesting expeditions.

The principal residence of the Elfords was at Longstone, in Sheeps Tor, where the old house remains little altered, and where the windstrew should be seen, a granite platform, raised above the field, on which thrashing could be carried on by the aid of the winds that carried away the chaff.

The tor which gives its name to the village and parish stands by itself, and rises to about 1,200 feet.

The Dewerstone

The basin below the village was anciently a lake, the water being retained by a barrier of rock where stands now the dam for the reservoir. This, in time, was silted up to the depth of ninety feet, and now the Plymouth Corporation, by the construction of a fine and eminently picturesque barrier across the narrow gorge through which the Meavy flows, have reconverted this basin into a lake.

Near the summit of the tor is the Pixy Cave, in which Squire Elford remained concealed whilst the Roundheads searched Longstone for him. Some faithful tenants in the village kept him supplied with food till pursuit was at an end. The Elfords inherited Longstone from the Scudamores at the close of the fifteenth century. The parish was then called Shettes Tor, from the Celtic syth, steep; but the name has been altered in this or last century. The last Elford of Sheeps Tor was John, who married Admonition Prideaux, and died without issue in 1748, his six children having predeceased him. A side branch of the family—to which, however, Sheeps Tor did not fall—produced Sir William Elford, Bart, of Bickham, but he died in 1837, without male issue, and the title became extinct. His monument is in Totnes church.

A man named Cole, working at the granite quarries at Merrivale Bridge, a few years ago sang me a song concerning a doe that escaped from Elford Park, which was probably situated where is now Yelverton.

THE SILLY DOE

Give ear unto my mournful song

Gay huntsmen every one,

And unto you I will relate

My sad and doleful moan.

O here I be a silly Doe,

From Elford Park I strayed,

In leaving of my company

Myself to death betrayed.

The master said I must be slain

For 'scaping from his bounds:

"O keeper, wind the hunting horn,

And chase him with your hounds."

A Duke of royal blood was there,

And hounds of noble race;

They gathered in a rout next day,

And after me gave chase.

They roused me up one winter morn,

The frost it cut my feet,

My red, red blood came trickling down,

And made the scent lie sweet.

For many a mile they did me run,

Before the sun went down,

Then I was brought to give a teen,

And fall upon the groun'.

The first rode up, it was the Duke:

Said he, "I'll have my will!"

A blade from out his belt he drew

My sweet red blood to spill.

So with good cheer they murdered me,

As I lay on the ground;

My harmless life it bled away,

Brave huntsmen cheering round.

Gay huntsmen every one,

And unto you I will relate

My sad and doleful moan.

O here I be a silly Doe,

From Elford Park I strayed,

In leaving of my company

Myself to death betrayed.

The master said I must be slain

For 'scaping from his bounds:

"O keeper, wind the hunting horn,

And chase him with your hounds."

A Duke of royal blood was there,

And hounds of noble race;

They gathered in a rout next day,

And after me gave chase.

They roused me up one winter morn,

The frost it cut my feet,

My red, red blood came trickling down,

And made the scent lie sweet.

For many a mile they did me run,

Before the sun went down,

Then I was brought to give a teen,

And fall upon the groun'.

The first rode up, it was the Duke:

Said he, "I'll have my will!"

A blade from out his belt he drew

My sweet red blood to spill.

So with good cheer they murdered me,

As I lay on the ground;

My harmless life it bled away,

Brave huntsmen cheering round.

I am a little puzzled as to whether the dry sarcasm in this song is intentional.[1] The melody is peculiarly sweet and plaintive. When a royal duke hunted last on Dartmoor I have been unable to ascertain.

The red deer were anciently common on Dartmoor. It was not till King John's reign that Devon was disafforested, with the exception of Dartmoor and Exmoor. But the deer were mischievous to the crops of the farmer, and to the young plantations, and farmers, yeomen, and squires combined to get rid of them from Dartmoor. Still, however, occasionally one runs from Exmoor and takes refuge in the woods about the Dart, the Plym, and the Tavy.

But it is for fox, hare, and otter hunting that the sportsman goes to Dartmoor, and not for the deer. A very pretty sight it is to see a pack with the scarlet coats after it sweeping over the moorside in pursuit of Reynard, and to hear the music of the hounds and horns.

For the harriers the great week is that after hare-hunting is at an end in the lowlands or "in-country." Then the several packs that have hunted through the season on the circumference of the moor unite on it, and take turns through the week on the moor itself. The great day of that week is Bellever Day, when the meet is on the tor of that name. I have described it in my Book of the West, and will not repeat what has been already related. But I will venture to quote an account of otter-hunting on the Dart from the pen of Mr. William Collier, than whom no one has been more of an enthusiast for sport on the moor.

"The West Dart is the perfection of a Dartmoor river, flowing bright and rapid over a bed of granite boulders richly covered with moss and lichen, its banks bedecked with ferns and wild flowers of the moor, and fringed with the bog-myrtle and withy.

"Water holds scent well, and the whiff so fragrant to the nose of the hound rises to the surface and floats down stream, calling forth his musical chant of praise. For this reason otter-hunters draw up stream, and before the lair of the otter is reached the welkin rings with the music of the pack. The otter has left his trail on the banks, and on the stones where he has landed when fishing, his spoor can be seen freshly printed on a sandy nook, and he is very likely to be found in a well-known and remarkably safe holt, as they call it in the West, about half a mile above Dart Meet, which he shares at times with foxes, though his access to it is under water, and theirs, of course, above. If he were but wise enough to stay there he might defy his legitimate

enemies to do their worst. But he knows not man or his little ways, and he has heard the unwonted strain of the hounds as they have been crying over his footsteps hard by. They mark him in his retreat, and the whole pack proclaim that he is in the otter's parlour, the strongest place on the river. It is in a large rock hanging over a deep, dark pool, in a corner made by a turn in the river, with an old battered oak tree growing somehow from the midst, and backed by a confused jumble of granite blocks. The artist and the fisherman both admire this spot, though for totally different reasons, but the hunter likes it not, for he knows too well that if he runs the fox or the otter here his sport is over. A fox or an otter if run here is likely to

Sheeps Tor

harrying awaits him for the next four hours. There immediately arises a yell of 'Hoo-gaze!' the view halloo of the otter-hunter, probably an older English hunting halloo than 'Tally ho!' and the din of the hounds and terriers, the human scream, and the horn, like Bedlam broken loose, which he hears behind him, make him hurry up-stream as best he may. The master of the hounds, if he knows his business, will now call for silence, and, taking out his watch, will give the otter what he calls a quarter of an hour's law. It is wonderful how fond sportsmen are of law; perhaps there is an affinity between prosecuting a case and pursuing a chase. He wants the otter to go well away from his parlour, and his object for the rest of the day will be to keep him out of it. If he is a real good sporting otter-hunter he will tell his field that he wants his hounds to kill the otter without assistance from them; for in the West of England the vice of mobbing the otter is too common, with half the field in the water, hooting, yelling, poking with otter-poles, mixing the wrong scent (their own) with the right, making the water muddy, and turning the river into a brawling brook with a vengeance. The true otter-hunter only wants his huntsman and whip, and perhaps a very knowing and trustworthy friend, besides himself, to help in hunting the otter with his hounds, and not with men. The master gives the chase a good quarter of an hour by the clock; and, leaving the unearthly, or perhaps too earthly sounds behind him, the otter makes up-stream as fast as he can go. It is surprising how far an otter can get in the time, but fear lends speed to his feet. Then begins the prettiest part of the sport. The hounds are laid on, they dash into the river, and instantly open in full cry. The water teems with the scent of the otter; but the deep pools, rapid stickles, and rocky boulders over which the river foams hinder the pace. There is ample time to admire the spirit-stirring and beautiful scene. The whole pack swimming a black-looking pool under a beetling tor in full chorus; now and then an encouraging note on the horn; the echoes of the deep valley; the foaming and roaring Dart flowing down from above; the rich colour from the fern, the gorse, the heather, the moss, and the wild flowers; a few scattered weather-beaten oaks and fir trees, and the stately tors aloft, striking on the eye and ear, make one feel that otter-hunting on Dartmoor is indeed a sport.

"The Dart is a large river, for a Dartmoor stream, and presents many obstacles to the hounds; but they pursue the chase for some distance, and at length stop and mark, as they did before. The otter has got out of hearing, and has rested in a lair known to him under the river-bank. The terriers and an otter-pole dislodge him, and the sport becomes fast and furious. He is seen in all directions, sometimes apparently in two places at once, which makes the novice think there are two or three otters afoot. 'Hoo-gaze!' is now often heard, as one or another catches sight of him, and the field become very noisy and excited. It is still the object to run him up-stream, whilst he now finds it easier to swim down. 'Look out below!' is therefore heard in the fine voice of the master. There is a trusty person down-stream watching a shallow stickle, where the otter must be seen if he passes. Suddenly the clamour ceases, and silence prevails. The otter has mysteriously disappeared, and he has to be fresh found. The master is in no hurry. There is too much scent in the water of various sorts, and he will be glad to pause till it has floated away. He takes his hounds down-stream. The trusty man says the otter has not passed; but this makes no difference. Some way further down, with a wave of his hand, he sends all the hounds into the river again with a dash. They draw up-stream again, pass the trusty man still at his post, and reach the spot where the otter vanished. The river is beautifully clear again, and an old hound marks. A good hour, perhaps, has been lost, or rather spent, since the otter disappeared, and here he has been in one of his under-water dry beds. He is routed out by otter-poles, and liveliness again prevails, especially when he takes to the land to get down-stream by cutting off a sharp curve in the river—a way he has learnt in his frogging expeditions—and the hounds run him then like a fox. He is only too glad to plunge headlong into the river again, and he has reached it below the trusty man, who, however, goes down to the next shallow, and takes with him some others to turn the otter up from his safe parlour. They are hunting him now in a long deep pool, where he shifts from bank to bank, moving under water whilst the hounds swim above. He has a large supply of air in his lungs, which he vents as he uses it, and which floats to the surface in a series of bubbles. Otter-hunters calls it his chain, and it follows him wherever he goes, betraying his track in the muddiest water. He craftily puts his nose, his nose only, up to get a fresh supply of air now and then, under a bush or behind a rock, and then owners of sharp eyes call 'Hoo-gaze!' He finds himself in desperate straits, and he makes up his mind to go for his parlour at all hazards; but the hounds catch sight of him in the shallow of the trusty man, and the chase comes to an end. Otters are never speared in the West."[2]

And now to return to Sheeps Tor and the picturesque village that nestles under it.

The one building-stone is granite, grey and soft of tone. The village is small, and consists of a few cottages about the open space before the church.

This latter is of the usual moorland type, and in the Perpendicular style. Observe above the porch the curious carved stone, formerly forming part of a sun-dial, and dated 1640. It represents wheat growing out of a skull, and bears the inscription—

"Mors janua vitæ."

Portion of Screen, Sheeps Tor

What of old times still remains is the bull-ring to the south-east of the church. On the churchyard wall sat the principal parishioners, as in a dress circle. Near by is S. Leonard's Well, but it possesses no architectural interest.

In Burra Tor Wood is a pretty waterfall. Burra Tor was the residence of Rajah Brooke when in England. It had been presented to him by the Baroness Burdett Coutts and other admirers. In Sheeps Tor churchyard he lies, but Burra Tor has been sold since his death.

Above the wood stands Roman's Cross, probably called after S. Rumon or Ruan, whose body lay at Tavistock. There is another on Lee Moor.

The drive from Douseland round Yennadon, above the dam and the reservoir, to Sheeps Tor village, is hardly to be surpassed for beauty anywhere on the moor.

A walk that will richly repay the pedestrian is one up the valley of the Narra Tor Brook, between Sheeps Tor and Down Tor. He follows the Devonport leat till he reaches the turn on the right to Nosworthy Bridge. He passes Vinneylake, where are two interesting caches, one cut out of the conglomerate rubble brought down from the decomposed rocks above. This is now used as a turnip-house, but it is to be suspected it was anciently employed as a private still-house. In a field hard by is another, more like some of the Cornish structural fogous. It is roofed over with slabs of granite.

The ascent of Deancombe presents many peeps of great beauty. At the farm the road comes to an end, and here the tor must be ascended. East of Down Tor is a very fine stone row, starting from a circle of stones inclosing a cairn, and extending in the direction of a large, much-disturbed cairn. There is a blocking-stone at the eastern end, and a menhir by the ring of stones at the west end of the row. The length is 1,175 feet.

I visited this row with the late Mr. Lukis in 1880, when we found that men had been recently engaged on the row with crowbars. They had thrown down the two largest stones at the head. We appealed to Sir Massey Lopes, and he stopped the destruction of the monument, and since then Mr. R. Burnard and I have re-erected the stones then thrown down.

On the slope of Coombshead Tor are numerous hut circles and a pound.

From the stone row a walk along the ridge of the moor leads to Nun's Cross. This bore on it the

inscription, "Crux Siwardi." It is very rude; it stands 7 feet 4 inches high, and is fixed in a socket cut in a block of stone sunk in the ground. It was overthrown and broken about 1846, but was restored by the late Sir Ralph Lopes. By whom and for what

On the Meavy

to decipher. On the other side of the cross is "BOC—LOND"—three letters forming one line, and the remaining four another, directly under it. The cross is alluded to in a deed of 1240 as then standing.

Nun's Cross is probably a corruption of Nant Cross, the cross at the head of the nant or valley. The whole of Newleycombe Lake has been extensively streamed. The hill to the north is dense with relics of an ancient people. Roundy Farm, now in ruins, takes its name from the pounds which contributed to form the walls of its inclosures, many of which follow the old circular erections that once inclosed a primeval village. The ruined farmhouse bears the initials of a Crymes, a family once as great as that of the Elfords, but now gone. It is interesting to know that the farmer's wife of Kingset, that now includes Roundy Farm, was herself a Crymes. One very perfect hut circle here was for long used as a potato garden.

Hard by is Clakeywell Pool, by some called Crazywell. It is an old mine-work, now filled with water. It covers nearly an acre, and the banks are in part a hundred feet high. According to popular belief, at certain times at night a loud voice is heard calling from the water in articulate tones, naming the next person who is to die in the parish. At other times what are heard are howls as of a spirit in torment. The sounds are doubtless caused by a swirl of wind in the basin that contains the pond. An old lady, now deceased, told me how that as a child she dreaded going near this tarn—she lived at Shaugh—fearing lest she should hear the voice calling her by name.

The idea of mysterious voices is a very old one. The schoolboy will recall the words of Virgil in the first Georgic:—

"Vox . . . per lucos vulgo exaudita silentes Ingens."

The "wisht hounds" that sweep overhead in the dark barking are brentgeese going north or returning south. They have given occasion to many stories of strange voices in the sky.

In Ceylon the devil-bird has been the source of much superstitious terror.

A friend who has long lived in Ceylon says: "Never shall I forget when first I heard it. I was at dinner, when suddenly the wildest, most agonised shrieks pierced my ear. I was under the impression that a woman was being murdered outside my house. I snatched up a cudgel and ran forth to her aid, but saw no one." The natives regard this cry of the mysterious devil-bird with the utmost fear. They believe that to hear it is a sure presage of death; and they are not wrong. When they have heard it, they pine to death, killed by their own conviction that life is impossible.

Autenrieth, professor and physician at Tübingen, in 1822 published a treatise on Aërial Voices, in which he collected a number of strange accounts of mysterious sounds heard in the sky, and which he thought could not all be deduced from the cries of birds at night. He thus generalises the sounds:—

"They are heard sometimes flying in this direction, then in the opposite through the air; mostly, they are heard as though coming down out of the sky; but at other times as if rising from the ground. They resemble occasionally various musical instruments; occasionally also the clash of arms, or the rattle of drums, or the blare of trumpets. Sometimes they are like the tramp of horses, or the discharge of distant artillery. But sometimes, also, they consist in an indescribably hollow, thrilling, sudden scream. Very commonly they resemble all kinds of animal tones, mostly the barking of dogs. Quite as often they consist in a loud call, so that the startled hearer believes himself to be called by name, and to hear articulate words addressed to him. In some instances, Greeks have believed they were spoken to in the language of Hellas, whereas Romans supposed they were addressed in Latin. The modern Highlanders distinctly hear their vernacular Gaelic. These aërial voices accordingly are so various that they can be interpreted differently, according to the language of the hearer, or his inner conception of what they might say."

The Jews call the mysterious voice that falls from the heaven Bathkol, and have many traditions relative to it. The sound of arms and of drums and artillery may safely be set down to the real vibrations of arms, drums, and artillery at a great distance, carried by the wind.

In the desert of Gobi, which divides the mountainous snow-clad plateau of Thibet from the milder regions of Asia, travellers assert that they have heard sounds high up in the sky as of the clash of arms or of musical martial instruments. If travellers fall to the rear or get separated from the caravan, they hear themselves called by name. If they go after the voice that summons them, they lose themselves in the desert. Sometimes they hear the tramp of horses, and taking it for that of their caravan, are drawn away, and wander from the right course and become hopelessly lost. The old Venetian traveller Marco Polo mentions these mysterious sounds, and says that they are produced by the spirits that haunt the desert. They are, however, otherwise explicable. On a vast plain the ear loses the faculty of judging direction and distance of sounds; it fails to possess, so to speak, acoustic perspective. When a man has dropped away from the caravan, his comrades call to him; but he cannot distinguish the direction whence their voices come, and he goes astray after them.

Rubruquis, whom Louis IX. sent in 1253 to the court of Mongu-Khan, the Mongol chief, says that in the Altai Mountains, that fringe the desert of Gobi, demons try to lure travellers astray. As he was riding among them one evening with his Mongol guide, he was exhorted by the latter to pray, because otherwise mishaps might occur through the demons that haunted the mountains luring them out of the right road.

Morier, the Persian traveller, at the beginning of this century speaks of the salt desert near Khom. On it, he says, travellers are led astray by the cry of the goblin Ghul, who, when he has enticed them from the road, rends them with his claws. Russian accounts of Kiev in the beginning of the nineteenth century mention an island lying in a salt marsh between the Caspian and the Aral Sea, where, in the evening, loud sounds are heard like the baying of hounds, and hideous cries as well; consequently the island is reputed to be haunted, and no one ventures near it.

That the Irish banshee may be traced to an owl admits of little doubt; the description of the cries so closely resembles what is familiar to those who live in an owl-haunted district, as to make the identification all but certain. Owls are capricious birds. One can never calculate on them for hooting. Weeks will elapse without their letting their notes be heard, and then all at once for a night or two they will be audible, and again become silent—even for months.

The river Dart is said to cry. The sound is a peculiarly weird one; it is heard only when the wind is blowing down its deep valley, and is produced by the compression of the air in the winding passage. Whether it is calling for its annual tribute of a human life, I do not know, but of the river it is said:—

"The Dart, the Dart—the cruel Dart

Every year demands a heart!"

Every year demands a heart!"

To return to our walk.

If the path be taken leading back to Nosworthy Bridge, beside and in the road will be seen several mould-stones for tin.

Leather Tor is a fine pile of ruined granite. I have been informed that great quantities of flints have been found there, showing that at this spot there was a manufacturing of silex weapons and tools.

From Sheeps Tor the Drizzlecombe remains are reached with great ease. Here, near a tributary of the Plym, are three stone rows and two fine menhirs, a kistvaen, a large tumulus, and beside the stream a blowing-house with its mould-stones. Two of the rows are single, but one is double for a portion of its length only. There are blocking-stones and menhirs to each. The row connected with the great menhir is 260 feet long.

Sheeps Tor has been brought into the world by the construction of the reservoir. Formerly it was a place very much left to itself. There the old fiddler hung on who played venerable tunes, to which the people danced their old country dances. These latter may still be seen there, but, alas! the aged fiddler is dead. At one time it was a great musical centre, and it was asserted that two-thirds of the male population were in the church choir, acting either as singers or as instrumentalists.

We will now turn our steps towards Meavy.

Here is a house that belonged to the Drake family, half pulled down, a village cross under a very ancient oak, and a church in good condition.

There is some very early rude carving at the chancel arch in a pink stone, whence derived has not been ascertained.

Marchant's Cross is at the foot of the steep ascent to Ringmoor Down. It is the tallest of all the moor crosses, being no less than 8 feet 2 inches in height.

Another cross is in the hedge on Lynch Common.

Trowlesworthy Warren is situated among hut circles and inclosures. There is a double stone row on the southern slope, but it has been sadly

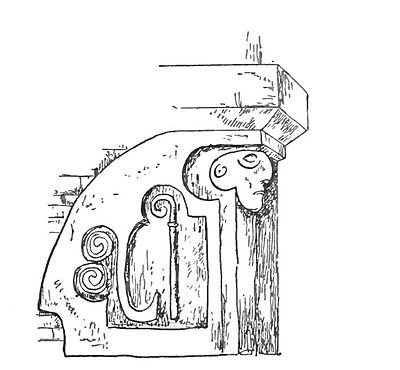

Chancel Capital, Meavy.

mutilated. The whole of the neighbouring moors are strewn with primeval habitations.

On Lee Moor and Headon Down may be seen the production of kaolin.

William Cookworthy, born at Kingsbridge in Devon, in 1705, was one of a large family. His father lost all his property in South Sea stock, and died leaving his widow to rear the children as best she might. They were Quakers, and help was forthcoming from the Friends. William kept his eyes about him, and discovered the china-clay which is found to so large an extent in Devon and Cornwall, and he laid the foundation of the kaolin trade between 1745 and 1750. One of the first places where he identified the clay was on Tregonning Hill in S. Breage parish, Cornwall, and to his dying day he was unaware of the enormous deposits on Lee Moor close to his Plymouth home.

He took out a patent in 1768 for the manufacture of Plymouth china, specimens of which are now eagerly sought after.

Kaolin is dissolved feldspar, deposited from the granite which has yielded to atmospheric and aqueous influences.

The white clay is dug out of pits and then is washed in tanks, in which the clayey sediment is collected. This sediment has, however, first to be purged of much of its mica and coarser particles as the stream in which it is dissolved is conveyed slowly over shallow "launders."

At the bottom of the pits are plugs, and so soon as the settled kaolin is sufficiently thick, these plugs are withdrawn, and the clay, now of the consistency of treacle, is allowed to flow into tanks at a lower level. Here it remains for three weeks or a month to thicken, when it is transferred to the "dry," a long shed with a well-ventilated roof, and with a furnace at one end and flues connected with it that traverse the whole "dry" and discharge into a chimney at the further end of the building. On the floor of this shed the clay rapidly dries, and it is then removed in spadefuls and packed in barrels or bags, or merely tossed into trucks for lading vessels. The clay is now white as snow, and is employed either in the Staffordshire potteries for the manufacture of porcelain, or else for bleaching—that is to say, for thickening calicoes, and for putting a surface on paper. Some is employed in the manufacture of alum; a good deal goes to Paris to be served up as the white sugar of confectionery, and it is hinted that not a little is employed in the adulteration of flour. America, as well, imports it for the manufacture of artificial teeth.

Great heaps of white refuse will be seen about the china-clay works; these are composed of the granitic sandy residuum. Of this there are several qualities, and it is sold to plasterers and masons, and the coarsest is gladly purchased for gravelling garden walks. The water that flows from the clay works is white as milk, and has a peculiar sweet taste. Cows are said to drink it with avidity. The full pans in drying present a metallic blue or green glaze on the surface.

The kaolin sent to Staffordshire travels by boat from Plymouth to Runcorn, where it is transhipped on to barges on the Bridgewater Canal, and is so conveyed to the belt of pottery towns, Burslem, Hanley, Stoke, and Longton.

The Dewerstone towers up at the junction of the Meavy and the Plym. On the side of the Plym there are sheer precipices of granite standing up as church spires above the brawling river. The face towards the Meavy is less abrupt, and it is on this side that an ascent can be made, but it is a scramble.

On reaching the top, it will be seen that the headland has been fortified by a double rampart of stone thrown across the neck of land. Wigford Down is in the rear, with kistvaens and tumuli and hut circles on it.

The visitor should descend in the direction of Goodameavy, and thence follow down the river that abounds in beautiful scenes. It was formerly believed that a wild hunter appeared on the summit of Dewerstone, attended by his black dogs, blowing a horn. From Dewerstone the visitor may walk to Bickleigh Station, and take the train for Tavistock, which I have written about in my Book of the West, and will not re-describe in the present work.