Thursday 24 May 2018

Friday 18 May 2018

mengele "energy of an infirm person" : annual summer solstice.

mengele "energy of an infirm person" : annual summer solstice.: Solstice sunrise at Stonehenge STONEHENGE: The sun rises behind the Stonehenge monument in England, during the summer solstice shortly a...

The archaeology of antimony

The archaeology of antimony mining: a resource assessment

In metallurgy, antimony was used in alloys for printer’s type, in the preparation of anti-friction metals and for hardening lead. It was also used as an alloy, at from 5 to 10 per cent, with tin in the production of Britannia metal. Antimony compounds were also used as a de-oxidiser and colourant in glass, pottery, pigments and dyes. From an early period antimony compounds were also used in cosmetics and for medicinal purposes, and, as such, can turn up in the archaeological record (Watson 2013, 21). A small number of mines in the 19th century and earlier, primarily in Cornwall, produced antimony concentrates as a co-product and a few were promoted with antimony as their principal product.

Geological background The principal ore of antimony is the sulphide stibnite (Sb2S3) although the antimony-lead sulphosalt (PB4FeSb6S14) has been worked in some mines. The antimony at the Louisa Mine, in Dumfries and Galloway, is associated with stratiform arsenopyrite-pyrite mineralisation in a Silurian greywacke sequence with similarities to that in the Clontibret area, County Monaghan (Gallagher et al. 1983, 24). The latter is associated with gold, and antimony has been associated with gold mineralisation in the vicinity of Port Isaac, Cornwall. Work by Clayton and others (1990) links the antimony in that part of Cornwall to stratiform pre-granite mineralisation and whilst there has been little or no investigation of antimony mineralisation in south-east Cornwall it is probably of a similar origin (See Scrivener and Shepherd 1998 on stratiform mineralisation in general in Cornwall). In Cumbria, to the north-east of Bassenthwaite, work by Fortey and others (1984) again links the antimony to stratiform mineralisation similar to that in Dumfries and Galloway.

Historical background Very few mines in Britain produced antimony ores in significant quantities and they appear to have been confined to Cornwall, Cumbria and parts of Scotland. Antimony mineral are reported elsewhere but with no known record of production. In Cornwall, at Wheal Leigh near Pillaton to the north-west of Saltash, antimony is said to have been worked from the late 16th century (Beer 1988, xxi). A mine or mines in the Pillaton area reportedly produced 25 tons of ore in the 1770s and over 130 tons of ore in the 1820s. Around Port Isaac in north Cornwall, and particularly in the parish of Endellion, antimony was being worked by the mid-18th century with production levels from Wheal Boys in the 1770s of around 95 tons (De La Beche 1839, 615-16). Lysons’ (1814, 194-216, citing Pryce, Mineralogia

2

Cornub.) noted that a works for producing regulus of antimony was set up by a Mr. Reed at Feock, close to Falmouth, and De La Beche (1839, 616) gives a date of 1778 for the works. A small number of mines in both these areas of Cornwall continued to produce small amounts of antimony ore in the second half of the 19th century (Burt et al 1987, xxxii). Small amounts of ore were also produced from mines in Cumbria, to the north-east Bassenthwaite on the western edge of the Caldbeck Fells. These were worked prior to 1816 (Lysons 1816, cxi) and again in the 1840s but information on the extent of those workings is limited. The best study of antimony mining and the processing of the ores in Britain comes from the southwest of Scotland and the working of the Louisa Mine at Glendining, in Dumfries and Galloway, and the work there can inform that which should be carried out in England. The history of the Louisa Mine, the antimony at which was first worked in 1793, was researched by McCracken (1965) at about the same period that it was examined by Charles Daniel in connection with other work in the area. Slag from the smelting process on site was analysed by Tylecote (1983), and the site was subsequently surveyed and included in the RCAHMS publication on the historic landscape of eastern Dumfrieshire (RCAHMS 1997, 276-77).

Technological background The mining and ore preparation methods employed in working antimony ores were little different to those used in the other hard rock non-ferrous metal mining sectors. Stibnite, the antimony sulphide, had a specific gravity well below that of galena, the lead sulphide, with which it was commonly found in mixed ore deposits and could therefore be easily separate by conventional methods. Jamesonite, the antimony-lead sulphosalt, was a different matter with the lead and antimony in chemical combination, where the antimony would be separated after smelting. Smelting of antimony ores to a metallic regulus was a specialist liquation process, carried out on site at Glendining in the 1790s and described in detail in the contemporary Statistical Account of Scotland (Sinclair 1791-99, II, 525-27). The process was evidently also carried out on at least one mine in Cornwall, Pengenna, near Port Isaac, where ‘old smelting works remain at Watergate, near the adit mouth, where much slag, rich in antimony, still lies’ (Dewey 1920, 50). Processing was also carried out at Feock in Cornwall, albeit away from the mining sites (Lysons 1814, 194-216) but little detail is available and the site of the process has not been investigated. Given that the presence of antimony could be a significant contaminant in lead, hardening it to the extent that it was brittle and no longer malleable; many producers were at pains to remove it. Softening hearths where antimony and other contaminants would be removed might be found at a number of lead smelters and Gill (2001, 95-96) describes such a hearth at Old Gang, Swaledale, confusingly known as the ‘Silver House’ although, as the process involved skimming contaminants from the surface of lead maintained in a molten state, it may have been confused with the Pattinson

3

process for silver enrichment. There is, however, no evidence that the antimony was recovered as a marketable product.

Infrastructure associated with antimony production There is no evidence of any elements within the infrastructure of mining in England which specifically supported the production of antimony. In Scotland, however, the settlement of Jamestown, in the parish of Westerkirk, Dumfries and Galloway, was built by the company operating the Louisa Mine in the 1790s along with an access road and bridges. The company also instituted a miners’ library in Jamestown which still survives (McCracken 1965, 143-44 and Appendix).

Archaeological assessment There has, as yet, been no archaeological investigation of antimony mines or the preparation and smelting of antimony ores in England. The limited amount of investigation done at Glendining, in Scotland, (RCAHMS 1997, 276-77) including analysis of the slag from the smelter carried out by Tylecote (1983), with the benefit of a contemporary account of operations in the 1790s (Sinclair 179199, II, 525-27), could provide information relevant to the investigation of sites in England.

Acknowledgements Thanks to Dave Williams and Mike Gill.

References Beer, K E 1988 The Metalliferous Mining Region of South-West England, addenda and corrigenda. Keyworth: BGS Clayton R E, Scrivener R C and Stanley C J 1990 ‘Mineralogical and preliminary fluid inclusion studies of leadantimony mineralisation in north Cornwall’ Proceedings of the Ussher Society 7.3, 258-62 http://ussher.org.uk/journal/90s/1990/documents/Clayton_et_al_1990.pdf [accessed 16 April 2013] De La Beche, H T 1839 Report on the Geology of Cornwall, Devon and West Somerset. London Dewey, H 1920 Arsenic and Antimony Ores, Memoirs of the Geological Survey, Special Reports on the Mineral Resources of Great Britain 15. London: HMSO Fortey N J, Ingham J D, Skilton, B R H, Young, B and Shepherd T, J 1984 ‘Antimony mineralisation at Wet Swine Gill’, Caldbeck Fells, Cumbria. Proc Yorkshire Geol Soc 45, 59-65 Gallagher, M J, Stone, P, Kemp, A E S, Hills, M G, Jones, R C, Smith, R T, Peachey, D Vickers, B P, Parker, M E, Rollin, K E and Skilton, B R H 1983 Stratabound arsenic and vein antimony mineralisation in

4

Silurian greywackes at Glendinning, south Scotland. London: BGS Mineral Reconnaissance Programme 59 [PDF document] URL http://nora.nerc.ac.uk/11855/1/WFMR83059.pdf [accessed 16 April 2013] Gill, M C 2001 Swaledale, its Mines and Smeltmills. Ashbourne: Landmark Lysons, D and Lysons, S 1816 Magna Britannia: volume 4: Cumberland. London [Web documents] http://www.british-history.ac.uk/source.aspx?pubid=404 [accessed 18 April 2013] McCracken, A 1965 ‘The Glendining Antimony Mine (Louisa Mine)’, Trans Dumfrieshire and Galloway Nat Hist and Antiq Soc, 3.42, 140-48 Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS) 1997 Eastern Dumfrieshire: an archaeological landscape. Edinburgh: HMSO Scrivener, R C and Shepherd, T J 1998 ‘Mineralization’ in E B Se1wood, E M Durrance and C M Bristow (eds) The Geology of Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly. 36-57. Exeter: UEP Sinclair, J 1791-99 Statistical Account of Scotland. 21 vols, Edinburgh Tylecote, R F 1983 ‘Scottish Antimony’ Proc Soc of Antiquaries of Scotland 113, 645-46 Watson, B 2013 ‘The Princess in the Police Station’, British Archaeology May-June 2013, 20-23

In metallurgy, antimony was used in alloys for printer’s type, in the preparation of anti-friction metals and for hardening lead. It was also used as an alloy, at from 5 to 10 per cent, with tin in the production of Britannia metal. Antimony compounds were also used as a de-oxidiser and colourant in glass, pottery, pigments and dyes. From an early period antimony compounds were also used in cosmetics and for medicinal purposes, and, as such, can turn up in the archaeological record (Watson 2013, 21). A small number of mines in the 19th century and earlier, primarily in Cornwall, produced antimony concentrates as a co-product and a few were promoted with antimony as their principal product.

Geological background The principal ore of antimony is the sulphide stibnite (Sb2S3) although the antimony-lead sulphosalt (PB4FeSb6S14) has been worked in some mines. The antimony at the Louisa Mine, in Dumfries and Galloway, is associated with stratiform arsenopyrite-pyrite mineralisation in a Silurian greywacke sequence with similarities to that in the Clontibret area, County Monaghan (Gallagher et al. 1983, 24). The latter is associated with gold, and antimony has been associated with gold mineralisation in the vicinity of Port Isaac, Cornwall. Work by Clayton and others (1990) links the antimony in that part of Cornwall to stratiform pre-granite mineralisation and whilst there has been little or no investigation of antimony mineralisation in south-east Cornwall it is probably of a similar origin (See Scrivener and Shepherd 1998 on stratiform mineralisation in general in Cornwall). In Cumbria, to the north-east of Bassenthwaite, work by Fortey and others (1984) again links the antimony to stratiform mineralisation similar to that in Dumfries and Galloway.

Historical background Very few mines in Britain produced antimony ores in significant quantities and they appear to have been confined to Cornwall, Cumbria and parts of Scotland. Antimony mineral are reported elsewhere but with no known record of production. In Cornwall, at Wheal Leigh near Pillaton to the north-west of Saltash, antimony is said to have been worked from the late 16th century (Beer 1988, xxi). A mine or mines in the Pillaton area reportedly produced 25 tons of ore in the 1770s and over 130 tons of ore in the 1820s. Around Port Isaac in north Cornwall, and particularly in the parish of Endellion, antimony was being worked by the mid-18th century with production levels from Wheal Boys in the 1770s of around 95 tons (De La Beche 1839, 615-16). Lysons’ (1814, 194-216, citing Pryce, Mineralogia

2

Cornub.) noted that a works for producing regulus of antimony was set up by a Mr. Reed at Feock, close to Falmouth, and De La Beche (1839, 616) gives a date of 1778 for the works. A small number of mines in both these areas of Cornwall continued to produce small amounts of antimony ore in the second half of the 19th century (Burt et al 1987, xxxii). Small amounts of ore were also produced from mines in Cumbria, to the north-east Bassenthwaite on the western edge of the Caldbeck Fells. These were worked prior to 1816 (Lysons 1816, cxi) and again in the 1840s but information on the extent of those workings is limited. The best study of antimony mining and the processing of the ores in Britain comes from the southwest of Scotland and the working of the Louisa Mine at Glendining, in Dumfries and Galloway, and the work there can inform that which should be carried out in England. The history of the Louisa Mine, the antimony at which was first worked in 1793, was researched by McCracken (1965) at about the same period that it was examined by Charles Daniel in connection with other work in the area. Slag from the smelting process on site was analysed by Tylecote (1983), and the site was subsequently surveyed and included in the RCAHMS publication on the historic landscape of eastern Dumfrieshire (RCAHMS 1997, 276-77).

Technological background The mining and ore preparation methods employed in working antimony ores were little different to those used in the other hard rock non-ferrous metal mining sectors. Stibnite, the antimony sulphide, had a specific gravity well below that of galena, the lead sulphide, with which it was commonly found in mixed ore deposits and could therefore be easily separate by conventional methods. Jamesonite, the antimony-lead sulphosalt, was a different matter with the lead and antimony in chemical combination, where the antimony would be separated after smelting. Smelting of antimony ores to a metallic regulus was a specialist liquation process, carried out on site at Glendining in the 1790s and described in detail in the contemporary Statistical Account of Scotland (Sinclair 1791-99, II, 525-27). The process was evidently also carried out on at least one mine in Cornwall, Pengenna, near Port Isaac, where ‘old smelting works remain at Watergate, near the adit mouth, where much slag, rich in antimony, still lies’ (Dewey 1920, 50). Processing was also carried out at Feock in Cornwall, albeit away from the mining sites (Lysons 1814, 194-216) but little detail is available and the site of the process has not been investigated. Given that the presence of antimony could be a significant contaminant in lead, hardening it to the extent that it was brittle and no longer malleable; many producers were at pains to remove it. Softening hearths where antimony and other contaminants would be removed might be found at a number of lead smelters and Gill (2001, 95-96) describes such a hearth at Old Gang, Swaledale, confusingly known as the ‘Silver House’ although, as the process involved skimming contaminants from the surface of lead maintained in a molten state, it may have been confused with the Pattinson

3

process for silver enrichment. There is, however, no evidence that the antimony was recovered as a marketable product.

Infrastructure associated with antimony production There is no evidence of any elements within the infrastructure of mining in England which specifically supported the production of antimony. In Scotland, however, the settlement of Jamestown, in the parish of Westerkirk, Dumfries and Galloway, was built by the company operating the Louisa Mine in the 1790s along with an access road and bridges. The company also instituted a miners’ library in Jamestown which still survives (McCracken 1965, 143-44 and Appendix).

Archaeological assessment There has, as yet, been no archaeological investigation of antimony mines or the preparation and smelting of antimony ores in England. The limited amount of investigation done at Glendining, in Scotland, (RCAHMS 1997, 276-77) including analysis of the slag from the smelter carried out by Tylecote (1983), with the benefit of a contemporary account of operations in the 1790s (Sinclair 179199, II, 525-27), could provide information relevant to the investigation of sites in England.

Acknowledgements Thanks to Dave Williams and Mike Gill.

References Beer, K E 1988 The Metalliferous Mining Region of South-West England, addenda and corrigenda. Keyworth: BGS Clayton R E, Scrivener R C and Stanley C J 1990 ‘Mineralogical and preliminary fluid inclusion studies of leadantimony mineralisation in north Cornwall’ Proceedings of the Ussher Society 7.3, 258-62 http://ussher.org.uk/journal/90s/1990/documents/Clayton_et_al_1990.pdf [accessed 16 April 2013] De La Beche, H T 1839 Report on the Geology of Cornwall, Devon and West Somerset. London Dewey, H 1920 Arsenic and Antimony Ores, Memoirs of the Geological Survey, Special Reports on the Mineral Resources of Great Britain 15. London: HMSO Fortey N J, Ingham J D, Skilton, B R H, Young, B and Shepherd T, J 1984 ‘Antimony mineralisation at Wet Swine Gill’, Caldbeck Fells, Cumbria. Proc Yorkshire Geol Soc 45, 59-65 Gallagher, M J, Stone, P, Kemp, A E S, Hills, M G, Jones, R C, Smith, R T, Peachey, D Vickers, B P, Parker, M E, Rollin, K E and Skilton, B R H 1983 Stratabound arsenic and vein antimony mineralisation in

4

Silurian greywackes at Glendinning, south Scotland. London: BGS Mineral Reconnaissance Programme 59 [PDF document] URL http://nora.nerc.ac.uk/11855/1/WFMR83059.pdf [accessed 16 April 2013] Gill, M C 2001 Swaledale, its Mines and Smeltmills. Ashbourne: Landmark Lysons, D and Lysons, S 1816 Magna Britannia: volume 4: Cumberland. London [Web documents] http://www.british-history.ac.uk/source.aspx?pubid=404 [accessed 18 April 2013] McCracken, A 1965 ‘The Glendining Antimony Mine (Louisa Mine)’, Trans Dumfrieshire and Galloway Nat Hist and Antiq Soc, 3.42, 140-48 Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS) 1997 Eastern Dumfrieshire: an archaeological landscape. Edinburgh: HMSO Scrivener, R C and Shepherd, T J 1998 ‘Mineralization’ in E B Se1wood, E M Durrance and C M Bristow (eds) The Geology of Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly. 36-57. Exeter: UEP Sinclair, J 1791-99 Statistical Account of Scotland. 21 vols, Edinburgh Tylecote, R F 1983 ‘Scottish Antimony’ Proc Soc of Antiquaries of Scotland 113, 645-46 Watson, B 2013 ‘The Princess in the Police Station’, British Archaeology May-June 2013, 20-23

Monday 7 May 2018

"PHŒNICIANS IN DART VALE.

Derivation of the name—Phœnicians—Taw Marsh—Artillery practice on the moors—Encroachments—The East Okement—Pounds and hut circles—Stone rows on Cosdon—Cranmere Pool—Sticklepath—Christian inscribed stones—South Zeal—West Wyke—North Wyke—The wicked Richard Weekes—South Tawton church—The West Okement—Yes Tor—Camp and Roman road—Throwleigh.

AGOOD deal of pseudo-antiquarianism has been expressed relative to the name of a little moorland parish two and a half miles uphill from Okehampton. It is now called Belstone, and it has been surmised that here stood a stone dedicated to Baal, whose worship had been introduced by the Phœnicians.

I must really quote one of the finest specimens of "exquisite fooling" I have ever come across. It appeared as a sub-article in the Western Morning News in 1890.

It was headed: —

"PHŒNICIANS IN DART VALE.

[SPECIAL.]

"Much interest, not only local but world-wide, was aroused a few months back by the announcement of a Phœnician survival at Ipplepen, in the person of Mr. Thomas Ballhatchet, descendant of the priest of the Sun Temple there, and until lately owner of the plot of land called Baalford, under Baal Tor, a priestly patrimony, which had come down to him through some eighteen or twenty centuries, together with his name and his marked Levantine features and characteristics.

"Such survivals are not infrequent among Orientals, as, for instance, the Cohens, Aaron's family, the Bengal Brahmins, the Rechabites, etc. Ballhatchet's sole peculiarity is his holding on to the land, in which, however, he is kept in countenance in England by the Purkises, who drew the body of Rufus to its grave in Winchester Cathedral on 2nd August, 1100.

"Further quiet research makes it clear beyond all manner of doubt that the Phœnician tin colony, domiciled at Totnes, and whose Sun Temple was located on their eastern sky-line at Ipplepen, have left extensive traces of their presence all the way down the Dart in the identical andunaltered names of places, a test of which the Palestine Exploration Committee record the priceless value. To give but one instance. The beautiful light-refracting diadem which makes Belliver[1] the most striking of all her sister tors, received from the Semite its consecration as 'Baallivyah,' Baal, crown of beauty or glory. The word itself occurs in Proverbs i. 9 and iv. 9, and as both Septuagint and Vulgate so render it, it must have borne that meaning in the third century B C., and in the third century A.D., and, of course, in the interval. There are many other instances quite as close, and any student of the new and fascinating science of Assyriology will continually add to them. A portrait of Ballhatchet, with some notes by an eminent and well-known Semitic scholar, may probably appear in the Graphic; in the meantime it may be pointed out that his name is typically Babylonian. Not only is there at Pantellaria the gravestone of one Baal-yachi (Baal's beloved), but no less than three clay tablets from the Sun Temple of Sippara (the Bible Sepharvaim) bear the names of Baal-achi-iddin, Baal-achi-utsur, and Baal-achi-irriba. This last, which bears date 22 Sivan (in the eleventh year of Nabonidus, B.C. 540), just two years before the catastrophe which followed on Belshazzar's feast, is in the possession of Mr. W. G. Thorpe, F.S.A. It is in beautiful condition, and records a loan by one Dinkiva to Baal-achi-irriba (Baal will protect his brother), on the security of some slaves."

One really wonders in reading such nonsense as this whether modern education is worth much, when a man could write such trash and an editor could admit it into his paper.

Ballhatchet means the hatchet or gate to a ball, i.e. a mine.

As it happens, there is not a particle of trustworthy evidence that the Phœnicians ever traded directly with Cornwall and Devon. The intermediary traders were the Veneti of what is now Vannes, and the tin trade was carried through Gaul to Marseilles, as is shown by traces left on the old trade route. In the next place, there is no evidence that our British or Ivernian ancestors ever heard the name of Baal. And finally, Belstone is not named after a stone at all, to return to the point whence we started. In Domesday it is Bellestham, or the ham, meadow of Belles or Bioll, a Saxon name that remains among us as Beale.

Belstone is situated at the lip of Taw Marsh, once a fine lake, with Steeperton Tor rising above it at the head. Partly because the river has fretted a way through the joints of the granite, forming Belstone Cleave, and partly on account of the silting up of the lake-bed with rubble brought down by the several streams that here unite, the lake-bed is now filled up with sand and gravel and swamp.

The military authorities coveted this tract for artillery practice. They set up butts, but woman intervened. A very determined lady marched up to them, although the warning red flags fluttered, and planted herself in front of a target, took out of her reticule a packet of ham sandwiches and a flask of cold tea, and declared her intention of spending the day there. In vain did the military protest, entreat, remonstrate; she proceeded to nibble at her sandwiches and defied them to fire.

She carried the day.

Since then Taw Marsh has been the playfield of many children, and has been rambled over by visitors, but the artillery have abstained from practising on it.

The fact is that the military have made the moors about Okehampton impossible for the visitor, and those who desire to rove over it in pursuit of health have been driven from Okehampton to Belstone, and object to be moved on further.

What with the camp at Okehampton and the prisons at Princetown and encroachments on every side, the amount of moorland left open to the rambler is greatly curtailed.

The privation is not only felt by the visitor but also by the farmer, who has a right to send out his sheep and cattle upon the moor in summer, and in times of drought looks to this upland as his salvation.

A comparison between what the Forest of Dartmoor was at the beginning of this century and its condition to-day shows how inclosures have crept on—nay, not crept, increased by leaps; and what is true of the forest is true also of the commons that surround it. Add to the inclosed land the large tract swept by the guns at Okehampton, and the case becomes more grave still. The public have been robbed of their rights wholesale. Not a word can now be raised against the military. The Transvaal War has brought home to us the need we have to become expert marksmen, and the Forest of Dartmoor seems to offer itself for the purpose of a practising-ground. Nevertheless, one accepts the situation with a sigh.

There is a charming excursion up the East Okement from the railway bridge to Cullever Steps, passing on the way a little fall of the river, not remarkable for height but for picturesqueness. There is no path, and the excursion demands exertion.

On Belstone Common is a stone circle and near it a fallen menhir. The circle is merely one of stones that formed a hut, which had upright slabs lining it within as well as girdling without.

Under Belstone Tor, among the "old men's workings" by the Taw, an experienced eye will detect a blowing-house, but it is much dilapidated.

The Taw and an affluent pour down from the central bog, one on each side of Steeperton Tor, and from the east the small brook dances into Taw Marsh. Beside the latter, on the slopes, are numerous pounds and hut circles, and near its source is a stone circle, of which the best uprights have been carried off for gateposts. South of it is a menhir, the Whitmoor Stone, leaning, as the ground about it is marshy. Cosdon, or, as it is incorrectly called occasionally, Cawsand, is a huge rounded hill ascending to 1,785 feet, crowned with dilapidated cairns and ruined kistvaens. East of the summit, near the turf track from South Zeal, is a cairn that contained three kistvaens. One is perfect, one wrecked, and of the third only the space remained and indications whence the slabs had been torn. From these three kistvaens in one mound start three stone rows that are broken through by the track, but can be traced beyond it for some way; they have been robbed, as the householders of South Zeal have been of late freely inclosing large tracts of their common, and have taken the stones for the construction of walls about their fields.

By ascending the Taw, Cranmere Pool may be reached, but is only so far worth the visit that the walk to and from it gives a good insight into the nature of the central bogs. The pool is hardly more than a puddle. Belstone church is not interesting; it was rebuilt, all but the tower, in 1881. Under Cosdon nestles Sticklepath. "Stickle" is the Devonshire for steep. Here is a holy well near an inscribed stone. A second inscribed stone is by the roadside to Okehampton. At Belstone are two more, but none of these bear names. They are Christian monuments of the sixth, or at latest seventh, century. At Sticklepath was a curious old cob thatched chapel, but this has been unnecessarily destroyed, and a modern erection of no interest or

Inscribed Stone, Sticklepath

beauty has taken its place. South Zeal is an interesting little village, through which ran the old high-road, but which is now left on one side. For long it was a treasury of interesting old houses; many have disappeared recently, but the "Oxenham Arms," the seat of the Burgoyne family, remains, the fine old village cross, and the chapel, of granite. Above South Zeal, on West Wyke Moor, is the house that belonged to the Battishill family, with a ruined cross near it. The house has been much spoiled of late; the stone mullions have been removed from the hall window, but the ancient gateway, surmounted by the Battishill arms, and with the date 1656, remains untouched. It is curious, because one would hardly have expected a country gentleman to have erected an embattled gateway during the Commonwealth, and in the style of the early Tudor kings. In the hall window are the arms of Battishill, impaled with a coat that cannot be determined as belonging to any known family. In the same parish of South Tawton is another old house, North Wyke, that belonged to the Wyke or Weekes family. The ancient gatehouse and chapel are interesting; they belong, in my opinion, to the sixteenth century, and to the latter part of the same. The chapel has a corbel, the arms of Wykes and Gifford; and John Wyke of North Wyke, who was buried in 1591, married the daughter of Sir Roger Gifford. The gateway can hardly be earlier. The house was built by the same man, but underwent great alteration in the fashion introduced from France by Charles II., when the rooms were raised and the windows altered into croisées.

Touching this house a tale is told.

About the year 1660 there was a John Weekes of North Wyke, who was a bachelor, and lived in the old mansion along with his sister Katherine, who was unmarried, and his mother. He was a man of weak intellect, and was consumptive. John came of age in 1658. In the event of his death without will his heir would be his uncle John, his father's brother, who died in 1680. This latter John had a son Roger.

Now it happened that there was a great scamp of the name of Richard Weekes, born at Hatherleigh, son of Francis Weekes of Honeychurch, possibly a remote connection, but not demonstrably so.

He was a gentleman pensioner of Charles II., but spent most of his leisure time in the Fleet Prison. One day this rascal came down from London, it is probable at the suggestion of consumptive John's mother and sister, who could not be sure what he, with his feeble mind, might do with the estate.

Richard ingratiated himself into the favour of John, and urged him not to risk his health in so bleak and exposed a spot as South Tawton, but to seek a warmer climate, and he invited him to Plymouth. The unsuspicious John assented.

When John was cajoled to Plymouth, Richard surrounded him with creatures of his own, a doctor and two lawyers, who, with Richard's assistance, coaxed, bullied, and persuaded the sickly John into making a deed of settlement of all his estate in favour of Richard. The unhappy man did this, but with a curious proviso enabling him to revoke his act by word as well as by deed. Richard had now completely outwitted John's mother and sister, who had been conspirators with him, on the understanding that they were to share the spoils.

After a while, when it was clear that John was

North Wyke Gate House

1661, but not till he had been induced by his mother and sister to revoke his will verbally, for they had now learned how that the wily Richard had got the better of them.

Next day, Sunday, Richard Weekes arrived, booted and spurred, at the head of a party of men he had collected. With sword drawn he burst into the house, and when Katherine Weekes attempted to bar the way he knocked her down. Then he drove the widow mother into a closet and locked the door on her. He now cleared the house of the servants, and proceeded to take possession of all the documents and valuables that the mansion contained. Poor John's body lay upstairs: no regard was paid to that, and, saying "I am come to do the devil's work and my own," he drove Katherine out of the house, and she was constrained to take refuge for the night in a neighbouring farm. The widow, Mary Weekes, was then liberated and also turned out of doors.

The heir-at-law was the uncle John, against whom Mary and Katherine Weekes had conspired with the scoundrel Richard. This latter now sought Uncle John, made him drunk, and got him to sign a deed, when tipsy, conveying all his rights to the said Richard for the sum of fifty pounds paid down. Richard was now in possession. The widow thereupon brought an action in Chancery against Richard. The lawyers saw the opportunity. Here was a noble estate that might be sucked dry, and they descended on it with this end in view.

The lawsuit was protracted for forty years, from 1661 to 1701, when the heirs of the wicked Richard retained the property, but it had been so exhausted and burdened, that the suit was abandoned undecided. Richard Weekes died in 1670.

The plan resorted to in order to keep possession after the forcible entry was this. The son of Richard Weekes had married a Northmore of Well, in South Tawton, and the Northmores bought up all the debts on the estate and got possession of the mortgages, and worked them persistently and successfully against the rightful claimants till, worried and wearied out, and with empty purses, they were unable further to pursue the claim. In 1713 the estate was sold by John Weekes, the grandson of Richard, who had also married a Northmore, and North Wyke passed away from the family after having been in its possession since the reign of Henry III.

It was broken up into two farms, and the house divided into two. Recently it has, however, been repurchased by a descendant of the original possessors, in a female line, the Rev. W. Wykes Finch, and the house is being restored in excellent taste.

In South Tawton church is a fine monument of the common ancestor, John Wyke, 1591. The church has been renovated, monumental slabs sawn in half and used to line the drain round the church externally. With the exception of the sun-dial, bearing the motto from Juvenal, "Obrepet non intellecta senectus" and a Burgoyne monument and that of "Warrior Wyke," the church does not present much of interest at present, whatever it may have done before it fell into the hands of spoilers.

The West Okement comes down from the central bogs through a fine "Valley of Rocks," dividing and forming an islet overgrown with wild rose and whortleberry. Above it stands Shilstone Tor, telling by its name that on it at one time stood a cromlech, which has been destroyed. This valley furnishes many studies for the artist.

Hence Yes Tor may be ascended, for long held to be the highest elevation on Dartmoor. The highest peak it is, rising to 2,030 feet, but it is over-topped by the rounded High Willhayes, 2,039 feet. Between Yes Tor and Mill Tor is a rather nasty bog. Mill Tor consists of a peculiar granite; the feldspar is so pure that speculators have been induced to attempt to make soda-water bottles out of it, by fusing without the adjunct of other materials.

On the extreme edge of a ridge above the East Okement, opposite Belstone Tor, is a camp, much injured by the plough. Apparently from it leads a paved raised causeway or road, presumed to be Roman; but why such a road should have been made from a precipitous headland above the Okement, and whither it led, are shrouded in mystery. Near this road, in 1897, was found a hoard of the smallest Roman coins, probably the store of some beggar, which he concealed under a rock, and died without being able to recover it. All pertained to the years between A.D. 320 and 330.

Of Okehampton I will say nothing here, as the place has had a chapter devoted to it in my Book of the West—too much space, some might say, for in itself it is devoid of interest. Its charm is in the scenery round, and its great attraction during the summer is the artillery camp on the down above Okehampton Park. On the other side of Belstone, Throwleigh may be visited, where there are numerous prehistoric relics. There were many others, but they have been destroyed, amongst others a fine inclosure like Grimspound, but more perfect, as the inclosing wall was not ruinous throughout, and the stones were laid in courses. The pulpit of Throwleigh church is made up of old bench-ends.

- Jump up↑ Belliver is a modern contraction of Bellaford, as Redever is Redaford.

TIN-STREAMING

Remains of the tin-streamers—Dartmoor stream tin—Lode tin—The dweller in the hut circles did not work the tin—The tin trade with Britain—How tin was extracted—A furnace—Deep Swincombe—Blowing-houses—The wheel introduced in the reign of Elizabeth—Japanese primitive method—Numerous blowing-house ruins—The tin-mould stones—Merrivale Bridge—King's Oven—Its present condition—Mining.

NO one who has eyes in his head, and considers what he sees, if he has been on Dartmoor, can have failed to observe how that every stream-bed has been turned over, and how that every hollow in a hillside is furrowed.

The tin-streamers who thus scarred the face of the moor carried on their works far down below where the rivers debouch from the moor on to the lowlands, but there the evidences of their toil have been effaced by culture.

The tin found in the detritus of streams is the oxide, and is far purer than tin found in the lode. Mining for tin was pursued on Dartmoor during the Middle Ages to a limited extent only, and solely when the stream tin was exhausted.

A very interesting excursion may be made from Douseland Station up the Meavy valley to Nosworthy

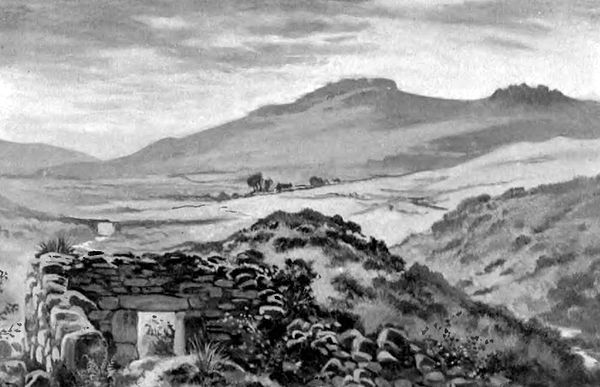

Blowing-house under Black Tor

Above this the stream has been turned about and

Tin-Workings, Nillacome.

its bed torn up, and rubble heaped in huge piles. Not only so, but the hillslope to the south is marked as with confluent smallpox, the result of the gropings of miners after tin. They followed up every trickle from the side and dug costeening, or shoding, pits everywhere in search of metal.

The upper waters of the Webburn have in like manner been explored, and some idea of the extent to which the moor was lacerated by the miners may be obtained from the Warren Inn on the road from Post Bridge to Moreton, looking east, when the slopes of Headland Warren and Challacombe will be seen seamed deeply.

The remains of the tinners have not been subjected to as full an exploration as they merit, but certain results have nevertheless been reached. One thing is abundantly clear, that all the tin-streaming was done subsequently to the time when men occupied the hut circles. The population living in them knew nothing of tin.

Diodorus Siculus, who wrote B.C. 8, says that the dwellers at Belerium, a cape of Britain, mined and smelted tin. "After beating it up into knucklebone shapes they carry it to a certain island lying off Britain, named Ictis, for at ebb tides, the space between drying up, they carry the tin in waggons thither . . . and thence the merchants buy it from the inhabitants and carry it over to Gaul, and lastly, travelling by land through Gaul about thirty days, they bring down the loads on horses to the mouth of the Rhine."

There can exist little doubt that Ictis is the same as Vectis, the Isle of Wight. It is held that anciently the island was connected with the mainland. The Roman station and harbour was at Brading. The early workers first pounded the ore with stone crushers, and such have been found. They then fanned it in the wind, which carried off the fine light dust, and left the metal on the shovels on which they tossed the ore and grit into the air. Beside some of the workings heaps of this dust have been detected. The washing of the ore came later. When sufficient had been collected, long troughs were sunk in the "calm," or native clay, and these were filled with charcoal; then the tin ore was laid on this charcoal, and either more of this latter was heaped above, or else peat was piled

Mortar-stone, Okeford.

up, with layers of ore. Finally the whole was kindled. No bellows were used, but a draught through the channel kept the whole glowing, and the metal ran through the fire into the bottom of the hollow, or ran out at the end, as this rude furnace was constructed on an incline.

In Staffordshire, at Kinver, and in the neighbourhood of Stourbridge, in Worcestershire, I have seen banks and hedges made up of what are locally called burrs. These consist of masses of sand and iron slag, two feet in diameter, round, and concave on one side, convex on the other. These burrs were formed in the primitive manufacture of iron, which much resembled that of tin. Andrew Yarranton, in England's Improvement by Sea and Land, 1698, says that he saw dug up near the walls of Worcester the hearth of an old Roman iron-furnace.

"It was an open hearth upon which was placed alternately charcoal and ironstone, to which fire being applied; it was urged by men treading upon bellows. The operation was very slow and imperfect. Unless the ore was very rich, not more than one hundredweight of iron could be extracted in a day. The ironstone did not melt, but was found at the bottom of the hearth in a large lump or bloom, which was afterwards taken out and beaten under massive hammers previous to its being worked into the required shape or form."

The burrs found are the sand and iron mixed that encased the bloom, which was taken out by pincers and worked on the anvil. The scoria that encased the bloom was thrown aside, and yet contains more than one-half of iron. The iron reduced in this simple manner never ran, but it became soft like dough, and could be removed and beaten into shape.

The method of dealing with the tin was similar, only that in this latter case the metal flowed. That foot bellows were employed before the system of working bellows, and producing a continuous blast by means of a water-wheel, is most probable. The foot bellows are known to most primitive people, but in Agricola's illustration of the smelting of tin

Slag-pounding Hollows, Gobbetts.

none are shown. On the contrary, Æolus is represented in the corner as blowing a natural blast.

The book of Agricola, published in 1556, shows that this primitive method was still in practice so late as the middle of the sixteenth century.

But this clumsy method could not be long practised on Dartmoor, where fuel—except peat—was scarce; and it gave way to a furnace of better construction, where the receiver was circular, and a draught-hole was at the bottom. One of these has

Smelting Ore. (After Agricola.)

been dug out and carefully examined at Deep Swincombe.

Plan of Blowing-house, Deep Swincombe.

At the extremity furthest from the door was a cache in the thickness of the wall, formed something like a kistvaen, as a place in which to store the metal and tools. The whole structure was banked up with rubble and turf.

Outside to the south still lies a mould-stone, a slab of elvan, in which the mould had been cut, measuring 26 inches long by 12 inches at one end and 15 at the other, and 5 inches deep.

That this is the earliest tin-furnace yet discovered on Dartmoor admits of no doubt. The curious mould-stone is quite different in shape from any others found on the moor. No mortar-stones were discovered, and this also is a token of antiquity.

The earliest smelting arrangements must have been very crude, and much tin was left in the slag. Until recently the Malays threw away their slags, which contained as much as 40 per cent of tin. As there have been no mortar-stones found at Deep Swincombe, it is to be presumed that the tinners disregarded their slags. These have not, moreover, been found. The reason was this—the sets had been reworked at a later time by the tinners at Gobbetts, further down the river. These later men had stone

Tin-mould, Deep Swincombe.

mortars and a crazing mill, and finding these rich slags, removed them, pounded them up in the hollowed mortar-stones, that may be seen in situ at Gobbetts, and resmelted them. Deep Swincombe has all the appearance of having been much pulled about by tinners since the first furnace was erected.

The tin running out of the furnace was allowed to flow into holes in the ground, and thence was ladled whilst in a molten condition and poured into the moulds.

Mr. Gowland has given a most interesting account of the manner in which the metals are extracted from their ores in Japan.[1] This shows how that the primitive methods are still in practice there. He says:—

"Although tin ore is found and worked in Japan in several localities, there is but one ancient mine in the country. It is situated in Taniyama, in the province of Satsuma. The excavations of the old miners here are of a most extensive character, the hillsides in places being literally honeycombed by their burrows, indicating the production in past times of large quantities of the metal. No remains, however, have been found to give any clue to the date of the earliest workings. But whatever may have been their date, the processes and appliances of the early smelters could not have been more primitive than those I found in use when I visited the mines in 1883.

"The ore was roughly broken up by hammers on stone anvils, then reduced to a coarse powder with the pounders used for decorticating rice, the mortars being large blocks of stone with roughly hollowed cavities.

"It was finally ground in stone querns, and washed by women in a stream to remove the earthy matter and foreign minerals with which it was contaminated. The furnace in which the ore was smelted is exactly the same as that used for copper ores, excepting that it is somewhat less in diameter. The ore was charged into it wet, in alternate layers with charcoal, and the process was conducted in precisely the same way as in smelting oxidised copper ores. The tin obtained was laded out of the furnace into moulds of clay."

The furnace employed for copper is also described by Mr. Gowland:—

"An excavation, measuring about 4 feet long, 4 feet wide, and 2 feet deep, is made, and this is filled with dry clay carefully beaten down. In the centre of this bed of clay a shallow, conical-shaped hole is scooped out. The hole is

Smelting Tin in Japan.

then lined with a layer, about three inches thick, of damp clay mixed with charcoal, and the furnace is complete.

"It has no apertures either for the injection of the blast or for tapping out the metal. A blast of air is supplied to it generally from two bellows, placed behind a wall of wattle well coated with clay, by which they and the men working them are protected from the heat. The blast is led from each bellows by a bamboo tube, terminating in a very long nozzle of clay, which rests on the edge of the furnace cavity."

At Deep Swincombe no bellows were used; the draught probably came in through the hole behind the furnace.

But in the reign of Queen Elizabeth a great revolution in the smelting of tin was wrought by the introduction of German workmen and their improved methods. They brought in the water-wheel. The ruins that are found in such abundance of "blowing-houses," as they are called—one at the least beside every considerable stream—belong, for the most part, to the Elizabethan period. They have their "leats" for carrying water to them, and their pits for tiny wheels that worked the bellows.

The situation of these smelting-houses may be found usually by the mould-stones that lie near them. There is one below the slide or fall of the Yealm, with its moulds in and by it, and another just above the fall. There is one near the megalithic remains at Drizzlecombe, also with its mould-stones. But it is unnecessary to particularise when they are so numerous. I will, however, quote Mr. R. Burnard's description of two in the Walkham valley as typical:

"The first is about 250 yards above Merrivale Bridge, on the left bank of the river. One jamb is erect, and, like most of the doorways of Dartmoor blowing-houses, was low, and to be entered necessitated an almost all-fours posture. Very little of the walls is standing, but what remains is composed of large moor-stones, dry laid. Near the entrance is a stone, 3 feet long and 2½ feet wide, containing a mould, which at the top is 18 inches long, 13 inches wide, and 6 inches deep. The sides are bevelled, so that the bottom length is 12½ inches, with a width of 7 inches at one end and 8 inches at the other. One end of the mould has a narrow gutter leading from the top to halfway down the mould. This was probably used for the insertion of a piece of iron prior to the metal being run in, thus permitting the easy withdrawal of the block of tin when cool from the mould. This stone also contains a small bevelled ingot or sample mould, 4 inches long, 2 inches wide, and 1¼ inches deep.

"A water-wheel probably stood in the eastern recess of the house, for there is a covered drain leading from here right under the house and out at the western end, where the water was discharged into the river. Traces of the leat which supplied the motive power to this wheel may also be seen.

"What appear to be the remains of the furnace, consisting of massive stones placed vertically, and inclosing a small rectangular space, are plainly visible. In this place, lying askew, as if it had been thrown out of position, is a large stone containing a long, shallow cavity, which may have been the bottom of the furnace or 'float,' i.e. the cavity in which the molten tin collected before being ladled into the mould.

"This ruin lies at the nether end of deep, open cuttings, which start from near Rundlestone Corner, and are continued right down to the Walkham.

"About 1,000 yards up stream is the ruin of the other blowing-house, with remains of a wheel-pit and a leat. There is also a stone containing a mould 16 inches long at the top, 11 inches wide, and 6 inches deep. It is bevelled, so that the bottom length is 12½ inches, with a width of 8 inches. Like the mould-stone in the ruin below, it contains a sample ingot mould 3½ inches long, 3 inches wide, and 2 inches deep. The remains in these ruins are very similar to each other, and these blow-houses were probably smelting during the same period, indicating that a considerable quantity of tin was raised in their neighbourhood."[2]

Anciently, before the introduction of the wheel, the smelting-place above all others was at King's Oven, or Furnum Regis, near the Warren Inn, between Post Bridge and Moreton. It is mentioned in the Perambulation of Dartmoor, made in 1240. It consists of a circular inclosure of about seventy-two yards in diameter, forming a pound, with the remains of a quadrangular building in it. The furnace itself was destroyed some years ago. When the inclosure was made it was carried to a cairn that was in part demolished, to serve to form the bank of the pound. This cairn was ringed about with upright stones, and contained a kistvaen. The latter was rifled, and most of the stones removed to form the walls; but a few of the inclosing uprights were not meddled with, and between two was found firmly wedged a beautiful flint scraper.

As the drift tin was exhausted, and the slag of the earlier miners was used up, it became necessary to run adits for tin, and work the veins. These adits remain in several places, and where they have been opened have yielded up iron bars and picks. But these are not more ancient than mediæval times, probably late in them. That gold was found in the granite rubble of the stream-beds is likely. A model of a gold-washing apparatus was found on the moor a few years ago. It was made of zinc.

According to an old Irish historical narrative, a bard was wont to carry a wand of "white bronze" or tin, and his shoes were also tin-plated.[3] One wonders whether at any time a bard thus shod and with his rod of office strode over Dartmoor and chanted historic ballads there!

For such as would care to see these dry bones of antiquarian research into the past of tin-streamers clothed with flesh, I must refer them to my novel of Guavas the Tinner, in which I have described the mode of life of the metal-seekers on the moor in the time of Elizabeth.

PRINCETOWN

PRINCETOWN

Sir Thomas Tyrwhitt and Princetown—A desolate spot—The prisons—Escapes—A burglary—Merrivale Bridge and its group of remains—Staple Tor—Walk up the Walkham to Merrivale Bridge— Harter Tor—Black Tor logan stone—Tor Royal—Wistman's Wood—Bairdown Man—Langstone Moor Circle—Fice's Well—Whitchurch—Archpriests—Heath and heather—Heather ale—White Heath.

KING LOUIS XIV. selected the most barren and intractable bit of land out of which to create Versailles, with its gardens, plantations, and palace; and Sir Thomas Tyrwhitt chose the most inhospitable site for the planting of a town. Sir Thomas was Black Rod, and Warden of the Stannaries. He was a man of a sanguine temperament, for he calculated on reaping gold where he sowed shillings, and that in Dartmoor bogs.

At his recommendation prisons were erected at Princetown in 1806, at a cost of £130,000, for the captives in the French and American wars. Sir George Magrath, M.D., the physician who presided over the medical department from 1814 until the close of the war, testified to the salubrity of the establishment.

"From personal correspondence with other establishments similar to Dartmoor, I presume the statistical record of that great tomb of the living (embosomed as it is in a desert and desolate waste of wild, and in the winter time terrible scenery, exhibiting the sublimity and grandeur occasionally of elemental strife, but never partaking of the beautiful of Nature; its climate, too, cheerless and hyperborean), with all its disadvantages, will show that the health of its incarcerated tenants, in a general way, equalled, if not surpassed, any war prison in England or Scotland. This might be considered an anomaly in sanitary history, when we reflect how ungenially it might be supposed to act on southern constitutions; for it was not unusual in the months of December and January for the thermometer to stand at thirty-three to thirty-five degrees below freezing, indicating cold almost too intense to support animal life. But the density of the congregated numbers in the prison created an artificial climate, which counteracted the torpifying effect of the Russian climate without. Like most climates of extreme heat or cold, the new-comers required a seasoning to assimilate their constitution to its peculiarities, in the progress of which indispositions, incidental to low temperature, assailed them; and it was an everyday occurrence among the reprobate and incorrigible classes of the prisoners, who gambled away their clothing and rations, for individuals to be brought up to the receiving room in a state of suspended animation, from which they were usually resuscitated by the process resorted to in like circumstances in frigid regions. I believe one death only took place during my sojourn at Dartmoor, from torpor induced by cold, and the profligate part of the French were the only sufferers. As soon as the system became acclimated to the region in which they lived, health was seldom disturbed."

There were from seven to nine thousand prisoners incarcerated in the old portion of the establishment. They were packed for the night in stages one above another, and we can well believe that by this means they "created an artificial climate," but it must have been an unsavoury as well as an unwholesome one.

Over the prison gates is the inscription "Parcere subjectis" and the discomfort of so many being crammed into insufficient quarters strikes us now, and renders the inscription ironical; but it was not so regarded or intended at the time. Our convicts are nursed in the lap of luxury as compared with the condition of the prisoners at the beginning of the century. But then the criminal is the spoiled child of the age, to be petted, and pampered, and excused.

A convict with one eye, his nose smashed on one side, with coarse fleshy lips, was accosted by the chaplain. "For what are you in here, my man?" "For bigamy," was the reply. "Twasn't my fault; the women would have me."

One marvels that such a deformed, plain spot as the col between the two Hessary Tors should have been selected for a town. The only reply one can give is that Sir Thomas Tyrwhitt and the Prince Regent would have it so. It is on the most inclement site that could have been selected, catching the clouds from the south-west, and condensing fog about it when everywhere else is clear. It is exposed equally to the north and east winds. It stands over fourteen hundred feet above the sea, above the sources of the Meavy, in the ugliest as well as least suitable situation that could have been selected; the site determined by Sir Thomas, so as to be near his granite quarries.

There have been various attempts made by prisoners to escape. One of the most desperate was in November, 1880, when a conspiracy had been organised among the convicts. At the time a good many were engaged in a granite quarry. They had agreed to make a sudden dash on the warders, overpower them, whilst in the quarry; and they chose for the attempt the day in the month on which the governor went to Plymouth to receive the money for payment of the officials, with intent to waylay, rob, and murder him, then to break up into parties of two, and disperse over the moor.

One of the conspirators betrayed them, so that the scheme was known. It was deemed advisable not in any way to alter the usual arrangements, lest this should inspire suspicion in the minds of the convicts. The warders, armed with rifles, who keep guard at a distance round the quarry, were told when they heard the chief warder's whistle to close round the quarry, and, if necessary, fire.

The gang was marched, as usual, under a slender escort, to the quarry, and work was begun as usual. All went well till suddenly the ringleader turned about and, with his crowbar, struck at the head warder and staggered him for the moment: he reeled and almost fell. Instantly the convict shouted to his fellows, "Follow me, boys! Hurrah for freedom!" And they made a dash for the entrance to the quarry.

Meanwhile the head warder had rallied sufficiently to whistle, but before the outer ring of guards appeared some of the under warders discharged their rifles at the two leading convicts. One fell dead, the other was riddled with shot, yet, strange to say, lived, and, I believe, is alive still.

Before the rest of the conspirators could master the warders in the quarry and get away, the men who had been summoned appeared on the edge of the hollow, that was like a crater, with their rifles aimed at the convicts, who saw the game was up, and submitted.

There are always some crooked minds and perverse spirits in England ready to side with the enemies of their country or of society, whether Boers or burglars; and so it was in this case. A great outcry was made at the shooting of the two ringleaders. If a warder had been killed, no pity would have been felt for him by these faddists. All their feelings of sympathy were enlisted on behalf of the wrongdoer.

A curious case occurred in 1895.

On March l0th, Sunday, at night, the chaplain, who lived in a house in the town, being unable to sleep, about half-past eleven went downstairs in his dressing-gown. He was surprised to notice a light approaching from the study. Then he observed a man emerge into the hall, holding a large clasp knife in his hand. On seeing the chaplain, whose name was Rickards, he uttered a yell, and rushed at him with the knife.

The chaplain, who maintained his nerve, said, "Stop this fooling, and come in here and let us have a little talk; you have clearly lost your way."

The fellow offered no resistance, and allowed himself to be led into the study, where the Rev. C. Rickards quietly seated himself on the table, and said to the burglar, "Now, we shall get on better if you give me up that knife." At the same time he took hold of the blade and attempted to gain possession of it. He had disengaged two of the man's fingers from it, when the fellow drew the knife away, thereby badly cutting the chaplain's hand. Mr. Rickards then jumped off the table, exclaiming, "This is not fair!"

"Look here," said the burglar, "I won't be took at no price," and flourished the knife defiantly. Noticing that the fellow's pockets bulged greatly, Mr. Rickards said, "You're not going out with my property," and closed with him, and endeavoured to put his hand into one of the pockets. The burglar resisted, and made for the door. Mr. Rickards now got near where his gun hung on the wall; he took it down, and clicked the hammer. The gun was not loaded. The burglar then blew out the candle he carried, and ran from the room. Mr. Rickards at once loaded his gun with cartridges, and followed the fellow into the passage. He still had his own candle alight. The man then bolted into the drawing-room, and endeavoured to open the window. The chaplain entered, and said, "Now bail up; up with your arms, or I shall fire."

Thereupon the burglar made a dash at him, head down, and the chaplain retreated, the man rushing after him. Mr. Rickards had no desire to fire, and as the fellow plunged past him, he struck at him with the gun, but missed him. The fellow then dashed through the doorway, and ran again into the study. The chaplain pursued him, and, standing in the doorway, said, "Now I have you. The gun is loaded, and I shall certainly fire if you come towards me."

The burglar stood for a moment eyeing him, and then made a leap at him with the uplifted knife; and Mr. Rickards fired at his legs. The man was hit, and staggered back against the mantelboard. The chaplain said, "Have you had enough?"

Again the fellow gathered himself up with raised knife to fall on him, when Mr. Rickards said coolly, "The other barrel is loaded, and I shall fire if you advance." The man, however, again came on, when the chaplain fired again, and hit the man in his right arm, and the knife fell. Mr. Rickards stooped, picked up the knife, closed it, and put it into his pocket. Then, thinking that there might be more than this one man engaged in the burglary, he reloaded his gun. The burglar now went down in a lump on the hearthrug, bleeding badly.

By this time the house was roused; the servants had taken alarm, and had sent for the warders, who arrived, and a doctor was summoned.

The fellow had been engaged in a good many robberies prior to this.

One night a couple of young convicts escaped, and obtained entrance into the doctor's house, where evidently a large supper party had been held, as the tables had not been cleared after the departure of the guests. Afterwards, when retaken, one of the men said:—

"Sir, it was just as though the doctor had made ready, and was expecting us to supper. The table was laid, and there were chickens and ham, tongue, and cold meats, with puddings, cakes, and decanters of wine, making our mouths fairly water. We ate and ate as only two hungry convicts could eat after the semi-starvation of prison diet. I could not look at a bit more when I had finished. 'Try just a leetle slice more of this ham,' said my chum. 'No, thank you, Bill; I couldn't eat another mouthful to save my life.' And so we left, and were caught on going out."

Soon after this the chaplain visited the fellow who had been recaptured, and seeing him depressed and in a very unhappy frame of mind, said to him, "Anything on your soul, man? Your conscience troubling you?"

"Terrible," answered the convict; "I shall never get over my self-reproach—not taking another slice of ham."

An old man succeeded in getting away in a fog; he ran as far as Ilsington before he was caught.

When brought back he was rather oddly attired, and amongst other things carried a labourer's hoe. This he employed vigorously when crossing fields, if anyone came in sight. When captured a farmer came to view him. "Why, drat it," he exclaimed, "that's the man I saw hoeing Farmer Coaker's stubble fields the other day. It struck me as something new in farming, and I was going to ask him what there was in it that he paid a labourer to hoe his stubbles." This same convict, who was acquainted with the neighbourhood, whilst temporarily at large paid a visit to his wife one night. He asked her to let him come into the house, telling who he was. "Not likely; you don't come in here. The policeman's about the place, and I don't want 'ee," was her cheering reply.

During another recent escape from Dartmoor an amusing incident occurred in a lonely lane on a dark night in the neighbourhood of Walkhampton. Two warders on guard mistook an inoffensive but partially inebriated farmer for the escaped convict, and he mistook them for a couple of runaways.

"Here he comes," exclaimed one warder to the other at the sound of approaching footsteps. "Now for him," as they both pounced out of the hedge where they had been in hiding, and seized hold of the man.

"Look here, my good fellows," he cried. "I know who you be. You be them two runaways from Princetown, and I'll give you all I've got, clothes and all, if only you won't murder me. I've got a wife and childer to home. I'm sure now I don't a bit mind goin' home wi'out any of my clothes on to my body. My wife'll forgive that, under the sarcumstances; but to go back wi'out nother my clothes nor my body either—that would be more nor my missus could bear and forgive. I'd niver hear the end of it."

Formerly the manner in which escapes were made was by the convicts when peat-cutting building up a comrade in a peat-stack, but the warders are now too much on the alert for this to take place successfully.

Such buildings as have been erected at Princetown are ugly. The only structure that is not so is the "Plume of Feathers," erected by the French prisoners. Every other house is hideous, and most hideous of all are the rows of residences recently erected for the warders, for they are pretentious as well as ugly.

Yet Princetown may serve as a centre for excursions, if the visitor can endure the intermittent rushes of the trippers on their "cherry-bangs," and the persistent presence of the convict. If he objects to these, he can find accommodation a couple of miles off, at Two Bridges; but if he desire creature comforts he is sure of good entertainment at Princetown.

The group of remains at Merrivale Bridge is within an easy walk. These are the most famous on Dartmoor—not for their size or consequence, but because most accessible, being beside the road. But the whole collection is happily very complete.

There is a menhir, a so-called sacred circle, stone rows, a kistvaen, a pound, hut circles, and a cairn.

The menhir was the starting-point of a stone row that has been plundered for the construction of a wall. The sacred circle is composed of very small stones, and probably at one time inclosed a cairn. The stone rows that exist are fairly perfect. Those on the south, a double row, start from a cairn at the west end that has been almost destroyed, and end in blocking-stones to the east. They are, however, interrupted by a small cairn within a ring of stones, and, curiously enough, much as at Chagford, another row starts near it at a tangent from a partly destroyed cairn. The double row runs 849 feet.

The north pair of rows is imperfect; it probably had a cairn at the west end, but of it no traces now

Staple Tor

A fine kistvaen, formerly in a cairn, lies to the south of the southern pair of rows. A few years ago a stonecutter at Merrivale Bridge took a gatepost out of the coverer. In this kistvaen have been found, though previously rifled, a flint knife and a polishing stone. There were formerly two large cairns near, but both have been destroyed by the road-makers, as have also many of the hut circles; a good many, however, yet remain, and some are inclosed within a pound. In this ground is an apple-crusher, like an upper millstone, that has been cut, but never removed, because the demand for these stones ceased with the introduction of the screw-press. Some ardent but not experienced antiquaries have supposed it to be a cromlech! As such it is figured in Major Hamilton Smith's plan of the remains in 1828.

The tor Over Tor, on the right-hand side of the road, was overthrown by some trippers the first swallows of a coming flight—early in the century.

The descent to Merrivale Bridge is fine; the bold tors of Roos and Staple stand up grandly above the Walkham river. Walkham, by the way, is Wallacombe, the valley of the Walla.

The flank of Mis Tor towards the river is strewn with inclosures and hut circles.

On Staple Tor is a so-called tolmen, a freak of nature, unassisted by art. Cox Tor beyond is crowned with cairns, but they have been rifled.

A very charming excursion may be made by following the Plymouth road to Peak Hill, then descending to Hockworthy Bridge, and ascending the river as best possible thence, by Woodtown to Merrivale Bridge. There is a lane above Ward Bridge that mounts the hillside on the east, and commands a fine view of Vixen Tor with Staple and Roos Tors behind. In the evening, when the valley is in purple shade, a flood of golden glory from the west illumines Vixen Tor, and this is the true light in which the river should be ascended. A so-called cyclopean bridge is passed that spans a stream foaming down to join the Walkham.

Walkhampton church need not arrest the pedestrian; it has a fine tower, but contains absolutely nothing of interest. Adjoining the churchyard is, however, a very early church house, probably more ancient than the present Perpendicular church.

Sampford Spiney has its village church, a quaint, small, old manor house, and a good tower to the church. It is somewhat curious that the dedication of neither of these churches is recorded.

Within an easy stroll of Princetown to the south is Harter Tor. There are here many hut circles, and below Harter Tor are stone avenues leading from cairns.

Black Tor, that looks down on these remains, is also above a blowing-house and miners' hut, not of an ancient date, as it had a chimney and fireplace. The mould-stone lies in the grass and weed.

Black Tor has on it a logan stone that can be rocked by taking hold of a natural handle. On its summit is a rock basin.

Old Blowing-house on the Meavy

worthy visited Dartmoor. Tradition tells of high revelry and debauches taking place on that occasion. Sir Thomas planted trees that are doing fairly well.

Blowing-house Below Black Tor.

In the valley of the West Dart, under Longaford and Littaford Tors, is Wistman's Wood, now sadly reduced in size. It has been assumed to be the last remains of the forest that once covered Dartmoor. But no forest ever did that; at all events no forest of trees. The ashes of the fires used by the primitive inhabitants show that peat was their principal fuel, and that what oak and alder they burned was small and stunted.

In the sheltered combes doubtless trees grew, but not to any height and size.

The early antiquaries, S. Rowe and E. Atkyns Bray, talked much tall nonsense about Wistman's Wood as a sacred grove, dedicated to the rites of Druidism, and of the collection of mistletoe from the boughs of the oaks. As it happens, there are no prehistoric monuments near the wood to indicate that it was held in reverence, and no mistletoe grows in Devon, and in Somersetshire only on apple trees. Indeed, the mistletoe will not grow higher than five or six hundred feet above the sea, and Wistman's Wood is not much less than a thousand feet above the sea-level.

In July, 1882, the central portion of the wood was set fire to, it was thought by trippers, in an attempt to boil a kettle. This has helped to reduce the ancient wood; but what prevents its increase is the sheep, which eat the young trees as they shoot up. It has been said that Wistman's Wood oaks produce no acorns. This, however, is not the case. The trees are so venerable that their power to bear fruit is nearly over, yet they still produce some acorns, and there are young oaks growing—but not where sheep roam—that have come from these parent stocks.

By ascending Bairdown, aiming for Lydford Tor, and then following the ridge almost due north, but with a little deflection to the west, Devil Tor may be reached, and near this stands the most impressive menhir on the moor, the Bairdown Man. The height is only twelve feet, but it is clothed in black lichen, and stands in such a solitary spot that it inevitably leaves an impression on the imagination. There is no token of there having ever been a stone row in connection with it.

It may here be noticed that the names Lydford Tor, Littaford, Longaford, Belleford, Reddaford, do not apply to any fords over the streams, which may be crossed without difficulty, but take their appellation from the Celtic fordd, "a way," and the tors about the Cowsick and West Dart take their titles from the great central causeway or from the Lych Way that passed by them.

The portion of the Cowsick above Two Bridges abounds in charming studies of river, rock, and timber.

An excursion to Great Mis Tor will enable the visitor to see a large rock basin, the Devil's Fryingpan as it is called, and then, if he descends Greenaball, where are cairns, he will see on the slope opposite him, beyond the Walkham, a large village, consisting of circular pounds and hut circles. On reaching the summit of the hill he will see a fine circle of upright stones. It was originally double, but nearly all the stones forming the outer ring have been removed. The rest were fallen, but have been re-erected by His Grace the Duke of Bedford.

In such a case there can be no arbitrary restoration, for the holes that served as sockets for the stones can always be found, together with the trigger-stones. Indeed, it is easy by the shape of the socket-holes to see in which way the existing stones were planted.

About half a mile to the north-west is the Langstone, which gives its name to this down; it is of a basaltic rock, and not, as is usual, of granite. Fice's Well, which I remember in the midst of moor, is now included within the newtake of the prisons, and a wall has been erected to protect it. This deprives it of much of its charm. It was erected by John Fitz in 1568. Cut on the granite coverer are the initials of John Fitz and the date.

The tradition is that John Fitz of Fitzford and his lady were once pixy-led whilst on Dartmoor. After long wandering in vain effort to find their way, they dismounted to rest their horses by a pure spring that bubbled up on a heathery hillside. There they quenched their thirst; but the water did more than that—it opened their eyes, and dispelled the pixy glamour that had been cast over them, so that at once they were able to take a right direction so as to reach Tavistock before dark night fell. In gratitude for this, John Fitz adorned the spring with a granite structure, on which were cut in low-relief his initials and the date of his adventure.

There are some old crosses that may be seen by such as are interested in these venerable relics. The Windy-post stands between Barn Hill and Feather Tor, and there are also two on Whitchurch Down. One of these, the more modern, of the fifteenth century, has lost its shaft, and is reduced to a head; but the other cross may, perhaps, date from the seventh century—it may even be earlier. Whitchurch was an archpriesthood; there were two of these in Devon and one in Cornwall. The origin of these archpriesthoods is probably this.

In Celtic countries the king liked to have his household priest, who ministered to the retinue and to his family. On the other hand, the tribe had its own saint, who was the ecclesiastical official for the tribe and educated the young.

As the kings increased in power, and the old tribal arrangement broke down, they had their household priests consecrated bishops, and the tribal lands were constituted their dioceses. But in Devon and Cornwall this could not be, as the Saxons took all power away from the native princes, and the Latin ecclesiastics would endure the peculiar ecclesiastical organisation of the Celts. The household priests of the conquered chieftains therefore simply remained as archpriests. The Saxon and then the Norman nobles were not averse from having their own chaplains free from episcopal jurisdiction, and in some places the archpriest remained on. But the bishops did not like them, and one by one gobbled them up. Whitchurch was regulated by Bishop Stapeldon in 1332. At present only one archpriesthood lingers on, that of Haccombe. At an episcopal visitation, when the name of the archpriest is recited by the episcopal official, he does not respond, as to answer the citation would be a recognition of the bishop's jurisdiction over Haccombe. The very fine piece of screen in Whitchurch was placed there by a former Lord Devon. It comes from Moreton Hampstead. When the dunderheads there cast it forth, the Earl secured it and placed it where it might be preserved and valued. It is of excellent work.

Before laying down my pen I feel that I have not done homage to that which, after all, gives the flavour of poetry to the moorland—the heath and heather. I was one day on the top of the coach from Holsworthy to Bude, between two Scotch ladies, and I put to them the question, "Which is heath and which heather—that with the large, or that with the small bells?" And Jennie, on my right, said: "The large bell—that is heather"; but Grizel, on my left, said: "Nay, the small bell—that is heather." As Scottish women were undecided, I referred to books, and take their decision. The large bell is heath; the ling, that is heather.

In old times, so it is said, the Picts made of the heather a most excellent beer, and the secret was preserved among them. Leyden says that when the Picts were exterminated, a father and son, who alone survived, were brought before Kenneth the Conqueror, who promised them life if they would divulge the secret of heather ale. As they remained silent, the son was put to death before the eyes of his father. This exercise of cruelty failed in its effect. "Sire," said the old Pict, "your threats might have influenced my son, but they have no effect on me." The king suffered the Pict to live, and the secret remained untold.

Ah, weel! the Scotch make up for their loss upon whisky.

A recent writer, referring to the story, says: "It is just possible that the grain of truth contained in the tradition may be, that all the northern nations, as the Swedes still do, used the narcotic gale (Myrica gale), which grows among the heather, to give bitterness and strength to the barley beer; and hence the belief that the beer was made chiefly of the heather itself."