PRINCETOWN

Sir Thomas Tyrwhitt and Princetown—A desolate spot—The prisons—Escapes—A burglary—Merrivale Bridge and its group of remains—Staple Tor—Walk up the Walkham to Merrivale Bridge— Harter Tor—Black Tor logan stone—Tor Royal—Wistman's Wood—Bairdown Man—Langstone Moor Circle—Fice's Well—Whitchurch—Archpriests—Heath and heather—Heather ale—White Heath.

KING LOUIS XIV. selected the most barren and intractable bit of land out of which to create Versailles, with its gardens, plantations, and palace; and Sir Thomas Tyrwhitt chose the most inhospitable site for the planting of a town. Sir Thomas was Black Rod, and Warden of the Stannaries. He was a man of a sanguine temperament, for he calculated on reaping gold where he sowed shillings, and that in Dartmoor bogs.

At his recommendation prisons were erected at Princetown in 1806, at a cost of £130,000, for the captives in the French and American wars. Sir George Magrath, M.D., the physician who presided over the medical department from 1814 until the close of the war, testified to the salubrity of the establishment.

"From personal correspondence with other establishments similar to Dartmoor, I presume the statistical record of that great tomb of the living (embosomed as it is in a desert and desolate waste of wild, and in the winter time terrible scenery, exhibiting the sublimity and grandeur occasionally of elemental strife, but never partaking of the beautiful of Nature; its climate, too, cheerless and hyperborean), with all its disadvantages, will show that the health of its incarcerated tenants, in a general way, equalled, if not surpassed, any war prison in England or Scotland. This might be considered an anomaly in sanitary history, when we reflect how ungenially it might be supposed to act on southern constitutions; for it was not unusual in the months of December and January for the thermometer to stand at thirty-three to thirty-five degrees below freezing, indicating cold almost too intense to support animal life. But the density of the congregated numbers in the prison created an artificial climate, which counteracted the torpifying effect of the Russian climate without. Like most climates of extreme heat or cold, the new-comers required a seasoning to assimilate their constitution to its peculiarities, in the progress of which indispositions, incidental to low temperature, assailed them; and it was an everyday occurrence among the reprobate and incorrigible classes of the prisoners, who gambled away their clothing and rations, for individuals to be brought up to the receiving room in a state of suspended animation, from which they were usually resuscitated by the process resorted to in like circumstances in frigid regions. I believe one death only took place during my sojourn at Dartmoor, from torpor induced by cold, and the profligate part of the French were the only sufferers. As soon as the system became acclimated to the region in which they lived, health was seldom disturbed."

There were from seven to nine thousand prisoners incarcerated in the old portion of the establishment. They were packed for the night in stages one above another, and we can well believe that by this means they "created an artificial climate," but it must have been an unsavoury as well as an unwholesome one.

Over the prison gates is the inscription "Parcere subjectis" and the discomfort of so many being crammed into insufficient quarters strikes us now, and renders the inscription ironical; but it was not so regarded or intended at the time. Our convicts are nursed in the lap of luxury as compared with the condition of the prisoners at the beginning of the century. But then the criminal is the spoiled child of the age, to be petted, and pampered, and excused.

A convict with one eye, his nose smashed on one side, with coarse fleshy lips, was accosted by the chaplain. "For what are you in here, my man?" "For bigamy," was the reply. "Twasn't my fault; the women would have me."

One marvels that such a deformed, plain spot as the col between the two Hessary Tors should have been selected for a town. The only reply one can give is that Sir Thomas Tyrwhitt and the Prince Regent would have it so. It is on the most inclement site that could have been selected, catching the clouds from the south-west, and condensing fog about it when everywhere else is clear. It is exposed equally to the north and east winds. It stands over fourteen hundred feet above the sea, above the sources of the Meavy, in the ugliest as well as least suitable situation that could have been selected; the site determined by Sir Thomas, so as to be near his granite quarries.

There have been various attempts made by prisoners to escape. One of the most desperate was in November, 1880, when a conspiracy had been organised among the convicts. At the time a good many were engaged in a granite quarry. They had agreed to make a sudden dash on the warders, overpower them, whilst in the quarry; and they chose for the attempt the day in the month on which the governor went to Plymouth to receive the money for payment of the officials, with intent to waylay, rob, and murder him, then to break up into parties of two, and disperse over the moor.

One of the conspirators betrayed them, so that the scheme was known. It was deemed advisable not in any way to alter the usual arrangements, lest this should inspire suspicion in the minds of the convicts. The warders, armed with rifles, who keep guard at a distance round the quarry, were told when they heard the chief warder's whistle to close round the quarry, and, if necessary, fire.

The gang was marched, as usual, under a slender escort, to the quarry, and work was begun as usual. All went well till suddenly the ringleader turned about and, with his crowbar, struck at the head warder and staggered him for the moment: he reeled and almost fell. Instantly the convict shouted to his fellows, "Follow me, boys! Hurrah for freedom!" And they made a dash for the entrance to the quarry.

Meanwhile the head warder had rallied sufficiently to whistle, but before the outer ring of guards appeared some of the under warders discharged their rifles at the two leading convicts. One fell dead, the other was riddled with shot, yet, strange to say, lived, and, I believe, is alive still.

Before the rest of the conspirators could master the warders in the quarry and get away, the men who had been summoned appeared on the edge of the hollow, that was like a crater, with their rifles aimed at the convicts, who saw the game was up, and submitted.

There are always some crooked minds and perverse spirits in England ready to side with the enemies of their country or of society, whether Boers or burglars; and so it was in this case. A great outcry was made at the shooting of the two ringleaders. If a warder had been killed, no pity would have been felt for him by these faddists. All their feelings of sympathy were enlisted on behalf of the wrongdoer.

A curious case occurred in 1895.

On March l0th, Sunday, at night, the chaplain, who lived in a house in the town, being unable to sleep, about half-past eleven went downstairs in his dressing-gown. He was surprised to notice a light approaching from the study. Then he observed a man emerge into the hall, holding a large clasp knife in his hand. On seeing the chaplain, whose name was Rickards, he uttered a yell, and rushed at him with the knife.

The chaplain, who maintained his nerve, said, "Stop this fooling, and come in here and let us have a little talk; you have clearly lost your way."

The fellow offered no resistance, and allowed himself to be led into the study, where the Rev. C. Rickards quietly seated himself on the table, and said to the burglar, "Now, we shall get on better if you give me up that knife." At the same time he took hold of the blade and attempted to gain possession of it. He had disengaged two of the man's fingers from it, when the fellow drew the knife away, thereby badly cutting the chaplain's hand. Mr. Rickards then jumped off the table, exclaiming, "This is not fair!"

"Look here," said the burglar, "I won't be took at no price," and flourished the knife defiantly. Noticing that the fellow's pockets bulged greatly, Mr. Rickards said, "You're not going out with my property," and closed with him, and endeavoured to put his hand into one of the pockets. The burglar resisted, and made for the door. Mr. Rickards now got near where his gun hung on the wall; he took it down, and clicked the hammer. The gun was not loaded. The burglar then blew out the candle he carried, and ran from the room. Mr. Rickards at once loaded his gun with cartridges, and followed the fellow into the passage. He still had his own candle alight. The man then bolted into the drawing-room, and endeavoured to open the window. The chaplain entered, and said, "Now bail up; up with your arms, or I shall fire."

Thereupon the burglar made a dash at him, head down, and the chaplain retreated, the man rushing after him. Mr. Rickards had no desire to fire, and as the fellow plunged past him, he struck at him with the gun, but missed him. The fellow then dashed through the doorway, and ran again into the study. The chaplain pursued him, and, standing in the doorway, said, "Now I have you. The gun is loaded, and I shall certainly fire if you come towards me."

The burglar stood for a moment eyeing him, and then made a leap at him with the uplifted knife; and Mr. Rickards fired at his legs. The man was hit, and staggered back against the mantelboard. The chaplain said, "Have you had enough?"

Again the fellow gathered himself up with raised knife to fall on him, when Mr. Rickards said coolly, "The other barrel is loaded, and I shall fire if you advance." The man, however, again came on, when the chaplain fired again, and hit the man in his right arm, and the knife fell. Mr. Rickards stooped, picked up the knife, closed it, and put it into his pocket. Then, thinking that there might be more than this one man engaged in the burglary, he reloaded his gun. The burglar now went down in a lump on the hearthrug, bleeding badly.

By this time the house was roused; the servants had taken alarm, and had sent for the warders, who arrived, and a doctor was summoned.

The fellow had been engaged in a good many robberies prior to this.

One night a couple of young convicts escaped, and obtained entrance into the doctor's house, where evidently a large supper party had been held, as the tables had not been cleared after the departure of the guests. Afterwards, when retaken, one of the men said:—

"Sir, it was just as though the doctor had made ready, and was expecting us to supper. The table was laid, and there were chickens and ham, tongue, and cold meats, with puddings, cakes, and decanters of wine, making our mouths fairly water. We ate and ate as only two hungry convicts could eat after the semi-starvation of prison diet. I could not look at a bit more when I had finished. 'Try just a leetle slice more of this ham,' said my chum. 'No, thank you, Bill; I couldn't eat another mouthful to save my life.' And so we left, and were caught on going out."

Soon after this the chaplain visited the fellow who had been recaptured, and seeing him depressed and in a very unhappy frame of mind, said to him, "Anything on your soul, man? Your conscience troubling you?"

"Terrible," answered the convict; "I shall never get over my self-reproach—not taking another slice of ham."

An old man succeeded in getting away in a fog; he ran as far as Ilsington before he was caught.

When brought back he was rather oddly attired, and amongst other things carried a labourer's hoe. This he employed vigorously when crossing fields, if anyone came in sight. When captured a farmer came to view him. "Why, drat it," he exclaimed, "that's the man I saw hoeing Farmer Coaker's stubble fields the other day. It struck me as something new in farming, and I was going to ask him what there was in it that he paid a labourer to hoe his stubbles." This same convict, who was acquainted with the neighbourhood, whilst temporarily at large paid a visit to his wife one night. He asked her to let him come into the house, telling who he was. "Not likely; you don't come in here. The policeman's about the place, and I don't want 'ee," was her cheering reply.

During another recent escape from Dartmoor an amusing incident occurred in a lonely lane on a dark night in the neighbourhood of Walkhampton. Two warders on guard mistook an inoffensive but partially inebriated farmer for the escaped convict, and he mistook them for a couple of runaways.

"Here he comes," exclaimed one warder to the other at the sound of approaching footsteps. "Now for him," as they both pounced out of the hedge where they had been in hiding, and seized hold of the man.

"Look here, my good fellows," he cried. "I know who you be. You be them two runaways from Princetown, and I'll give you all I've got, clothes and all, if only you won't murder me. I've got a wife and childer to home. I'm sure now I don't a bit mind goin' home wi'out any of my clothes on to my body. My wife'll forgive that, under the sarcumstances; but to go back wi'out nother my clothes nor my body either—that would be more nor my missus could bear and forgive. I'd niver hear the end of it."

Formerly the manner in which escapes were made was by the convicts when peat-cutting building up a comrade in a peat-stack, but the warders are now too much on the alert for this to take place successfully.

Such buildings as have been erected at Princetown are ugly. The only structure that is not so is the "Plume of Feathers," erected by the French prisoners. Every other house is hideous, and most hideous of all are the rows of residences recently erected for the warders, for they are pretentious as well as ugly.

Yet Princetown may serve as a centre for excursions, if the visitor can endure the intermittent rushes of the trippers on their "cherry-bangs," and the persistent presence of the convict. If he objects to these, he can find accommodation a couple of miles off, at Two Bridges; but if he desire creature comforts he is sure of good entertainment at Princetown.

The group of remains at Merrivale Bridge is within an easy walk. These are the most famous on Dartmoor—not for their size or consequence, but because most accessible, being beside the road. But the whole collection is happily very complete.

There is a menhir, a so-called sacred circle, stone rows, a kistvaen, a pound, hut circles, and a cairn.

The menhir was the starting-point of a stone row that has been plundered for the construction of a wall. The sacred circle is composed of very small stones, and probably at one time inclosed a cairn. The stone rows that exist are fairly perfect. Those on the south, a double row, start from a cairn at the west end that has been almost destroyed, and end in blocking-stones to the east. They are, however, interrupted by a small cairn within a ring of stones, and, curiously enough, much as at Chagford, another row starts near it at a tangent from a partly destroyed cairn. The double row runs 849 feet.

The north pair of rows is imperfect; it probably had a cairn at the west end, but of it no traces now

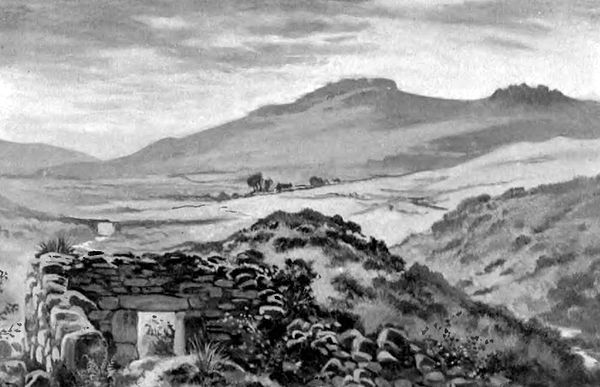

Staple Tor

A fine kistvaen, formerly in a cairn, lies to the south of the southern pair of rows. A few years ago a stonecutter at Merrivale Bridge took a gatepost out of the coverer. In this kistvaen have been found, though previously rifled, a flint knife and a polishing stone. There were formerly two large cairns near, but both have been destroyed by the road-makers, as have also many of the hut circles; a good many, however, yet remain, and some are inclosed within a pound. In this ground is an apple-crusher, like an upper millstone, that has been cut, but never removed, because the demand for these stones ceased with the introduction of the screw-press. Some ardent but not experienced antiquaries have supposed it to be a cromlech! As such it is figured in Major Hamilton Smith's plan of the remains in 1828.

The tor Over Tor, on the right-hand side of the road, was overthrown by some trippers the first swallows of a coming flight—early in the century.

The descent to Merrivale Bridge is fine; the bold tors of Roos and Staple stand up grandly above the Walkham river. Walkham, by the way, is Wallacombe, the valley of the Walla.

The flank of Mis Tor towards the river is strewn with inclosures and hut circles.

On Staple Tor is a so-called tolmen, a freak of nature, unassisted by art. Cox Tor beyond is crowned with cairns, but they have been rifled.

A very charming excursion may be made by following the Plymouth road to Peak Hill, then descending to Hockworthy Bridge, and ascending the river as best possible thence, by Woodtown to Merrivale Bridge. There is a lane above Ward Bridge that mounts the hillside on the east, and commands a fine view of Vixen Tor with Staple and Roos Tors behind. In the evening, when the valley is in purple shade, a flood of golden glory from the west illumines Vixen Tor, and this is the true light in which the river should be ascended. A so-called cyclopean bridge is passed that spans a stream foaming down to join the Walkham.

Walkhampton church need not arrest the pedestrian; it has a fine tower, but contains absolutely nothing of interest. Adjoining the churchyard is, however, a very early church house, probably more ancient than the present Perpendicular church.

Sampford Spiney has its village church, a quaint, small, old manor house, and a good tower to the church. It is somewhat curious that the dedication of neither of these churches is recorded.

Within an easy stroll of Princetown to the south is Harter Tor. There are here many hut circles, and below Harter Tor are stone avenues leading from cairns.

Black Tor, that looks down on these remains, is also above a blowing-house and miners' hut, not of an ancient date, as it had a chimney and fireplace. The mould-stone lies in the grass and weed.

Black Tor has on it a logan stone that can be rocked by taking hold of a natural handle. On its summit is a rock basin.

Old Blowing-house on the Meavy

worthy visited Dartmoor. Tradition tells of high revelry and debauches taking place on that occasion. Sir Thomas planted trees that are doing fairly well.

Blowing-house Below Black Tor.

In the valley of the West Dart, under Longaford and Littaford Tors, is Wistman's Wood, now sadly reduced in size. It has been assumed to be the last remains of the forest that once covered Dartmoor. But no forest ever did that; at all events no forest of trees. The ashes of the fires used by the primitive inhabitants show that peat was their principal fuel, and that what oak and alder they burned was small and stunted.

In the sheltered combes doubtless trees grew, but not to any height and size.

The early antiquaries, S. Rowe and E. Atkyns Bray, talked much tall nonsense about Wistman's Wood as a sacred grove, dedicated to the rites of Druidism, and of the collection of mistletoe from the boughs of the oaks. As it happens, there are no prehistoric monuments near the wood to indicate that it was held in reverence, and no mistletoe grows in Devon, and in Somersetshire only on apple trees. Indeed, the mistletoe will not grow higher than five or six hundred feet above the sea, and Wistman's Wood is not much less than a thousand feet above the sea-level.

In July, 1882, the central portion of the wood was set fire to, it was thought by trippers, in an attempt to boil a kettle. This has helped to reduce the ancient wood; but what prevents its increase is the sheep, which eat the young trees as they shoot up. It has been said that Wistman's Wood oaks produce no acorns. This, however, is not the case. The trees are so venerable that their power to bear fruit is nearly over, yet they still produce some acorns, and there are young oaks growing—but not where sheep roam—that have come from these parent stocks.

By ascending Bairdown, aiming for Lydford Tor, and then following the ridge almost due north, but with a little deflection to the west, Devil Tor may be reached, and near this stands the most impressive menhir on the moor, the Bairdown Man. The height is only twelve feet, but it is clothed in black lichen, and stands in such a solitary spot that it inevitably leaves an impression on the imagination. There is no token of there having ever been a stone row in connection with it.

It may here be noticed that the names Lydford Tor, Littaford, Longaford, Belleford, Reddaford, do not apply to any fords over the streams, which may be crossed without difficulty, but take their appellation from the Celtic fordd, "a way," and the tors about the Cowsick and West Dart take their titles from the great central causeway or from the Lych Way that passed by them.

The portion of the Cowsick above Two Bridges abounds in charming studies of river, rock, and timber.

An excursion to Great Mis Tor will enable the visitor to see a large rock basin, the Devil's Fryingpan as it is called, and then, if he descends Greenaball, where are cairns, he will see on the slope opposite him, beyond the Walkham, a large village, consisting of circular pounds and hut circles. On reaching the summit of the hill he will see a fine circle of upright stones. It was originally double, but nearly all the stones forming the outer ring have been removed. The rest were fallen, but have been re-erected by His Grace the Duke of Bedford.

In such a case there can be no arbitrary restoration, for the holes that served as sockets for the stones can always be found, together with the trigger-stones. Indeed, it is easy by the shape of the socket-holes to see in which way the existing stones were planted.

About half a mile to the north-west is the Langstone, which gives its name to this down; it is of a basaltic rock, and not, as is usual, of granite. Fice's Well, which I remember in the midst of moor, is now included within the newtake of the prisons, and a wall has been erected to protect it. This deprives it of much of its charm. It was erected by John Fitz in 1568. Cut on the granite coverer are the initials of John Fitz and the date.

The tradition is that John Fitz of Fitzford and his lady were once pixy-led whilst on Dartmoor. After long wandering in vain effort to find their way, they dismounted to rest their horses by a pure spring that bubbled up on a heathery hillside. There they quenched their thirst; but the water did more than that—it opened their eyes, and dispelled the pixy glamour that had been cast over them, so that at once they were able to take a right direction so as to reach Tavistock before dark night fell. In gratitude for this, John Fitz adorned the spring with a granite structure, on which were cut in low-relief his initials and the date of his adventure.

There are some old crosses that may be seen by such as are interested in these venerable relics. The Windy-post stands between Barn Hill and Feather Tor, and there are also two on Whitchurch Down. One of these, the more modern, of the fifteenth century, has lost its shaft, and is reduced to a head; but the other cross may, perhaps, date from the seventh century—it may even be earlier. Whitchurch was an archpriesthood; there were two of these in Devon and one in Cornwall. The origin of these archpriesthoods is probably this.

In Celtic countries the king liked to have his household priest, who ministered to the retinue and to his family. On the other hand, the tribe had its own saint, who was the ecclesiastical official for the tribe and educated the young.

As the kings increased in power, and the old tribal arrangement broke down, they had their household priests consecrated bishops, and the tribal lands were constituted their dioceses. But in Devon and Cornwall this could not be, as the Saxons took all power away from the native princes, and the Latin ecclesiastics would endure the peculiar ecclesiastical organisation of the Celts. The household priests of the conquered chieftains therefore simply remained as archpriests. The Saxon and then the Norman nobles were not averse from having their own chaplains free from episcopal jurisdiction, and in some places the archpriest remained on. But the bishops did not like them, and one by one gobbled them up. Whitchurch was regulated by Bishop Stapeldon in 1332. At present only one archpriesthood lingers on, that of Haccombe. At an episcopal visitation, when the name of the archpriest is recited by the episcopal official, he does not respond, as to answer the citation would be a recognition of the bishop's jurisdiction over Haccombe. The very fine piece of screen in Whitchurch was placed there by a former Lord Devon. It comes from Moreton Hampstead. When the dunderheads there cast it forth, the Earl secured it and placed it where it might be preserved and valued. It is of excellent work.

Before laying down my pen I feel that I have not done homage to that which, after all, gives the flavour of poetry to the moorland—the heath and heather. I was one day on the top of the coach from Holsworthy to Bude, between two Scotch ladies, and I put to them the question, "Which is heath and which heather—that with the large, or that with the small bells?" And Jennie, on my right, said: "The large bell—that is heather"; but Grizel, on my left, said: "Nay, the small bell—that is heather." As Scottish women were undecided, I referred to books, and take their decision. The large bell is heath; the ling, that is heather.

In old times, so it is said, the Picts made of the heather a most excellent beer, and the secret was preserved among them. Leyden says that when the Picts were exterminated, a father and son, who alone survived, were brought before Kenneth the Conqueror, who promised them life if they would divulge the secret of heather ale. As they remained silent, the son was put to death before the eyes of his father. This exercise of cruelty failed in its effect. "Sire," said the old Pict, "your threats might have influenced my son, but they have no effect on me." The king suffered the Pict to live, and the secret remained untold.

Ah, weel! the Scotch make up for their loss upon whisky.

A recent writer, referring to the story, says: "It is just possible that the grain of truth contained in the tradition may be, that all the northern nations, as the Swedes still do, used the narcotic gale (Myrica gale), which grows among the heather, to give bitterness and strength to the barley beer; and hence the belief that the beer was made chiefly of the heather itself."

I do not hold this. I suspect that the ale was metheglin, made of the honey extracted from the heather by the bees. Metheglin is still made round Dartmoor, but it is only good and "heady" when many years old. Avoid that which is younger than three winters. When it is older, drink sparingly.[1]

It is quite certain that the ancient Irish brewed a beer, which we can hardly think came from barley. S. Bridget has left but one poetical composition behind her, and that begins:—

"I should like a great lake of ale

For the King of kings.

I should like the whole company of Heaven

To be drinking it eternally!"

For the King of kings.

I should like the whole company of Heaven

To be drinking it eternally!"

The heath was doubtless largely used in former times, from the Prehistoric Age, not only as a thatch for the huts and hovels, but as a litter for the beds. Indeed, heath or heather is still employed in the Scottish Highlands along with the peat earth as a substitute for mortar between the stones of which a cottage is built. And that heather was employed for bedding who can question? Leather is tanned even better with heath than with oak-bark, and of it a brilliant yellow dye is produced.

But—ah, me! the heath and the heather!—it is not for the beer produced therefrom, not for the tan, not for the dye, that we love it. Wonderful is the sight of the moorside flushed with pink when the heather is in bloom—it is as though, like a maiden, it had suddenly awoke to the knowledge that it was lovely, and blushed with surprise and pleasure at the discovery.

But how shortlived is the heath!

It lies dead—a warm chocolate-brown, mantling the hills from October till July. Only in the midsummer does it timidly put forth its leaves—its spines rather—and then it flushes again in September. It blooms for about a fortnight, perhaps three weeks, and then subsides into its brown winter sleep. But what browns! what splendours of colour we have when the fern is in its russet decay and the heather is in its velvet sleep!

To him who wanders over the moor, and looks at the flowers at his feet, some day comes the proud felicity of lighting on the white heath—and that found ensures happiness. And I, as I make my congé, hand it to my reader with best wishes for his enjoyment of that region I love best in the world.

- ↑ Yet there is the Devonshire white ale—the composition of which is a secret—that is still drunk in the South Hams, and in one tavern in Tavistock. It is a singular, curdy liquor, in the manufacture of which egg is employed. Is heath used also? Quien sabe?