Remains of the tin-streamers—Dartmoor stream tin—Lode tin—The dweller in the hut circles did not work the tin—The tin trade with Britain—How tin was extracted—A furnace—Deep Swincombe—Blowing-houses—The wheel introduced in the reign of Elizabeth—Japanese primitive method—Numerous blowing-house ruins—The tin-mould stones—Merrivale Bridge—King's Oven—Its present condition—Mining.

NO one who has eyes in his head, and considers what he sees, if he has been on Dartmoor, can have failed to observe how that every stream-bed has been turned over, and how that every hollow in a hillside is furrowed.

The tin-streamers who thus scarred the face of the moor carried on their works far down below where the rivers debouch from the moor on to the lowlands, but there the evidences of their toil have been effaced by culture.

The tin found in the detritus of streams is the oxide, and is far purer than tin found in the lode. Mining for tin was pursued on Dartmoor during the Middle Ages to a limited extent only, and solely when the stream tin was exhausted.

A very interesting excursion may be made from Douseland Station up the Meavy valley to Nosworthy

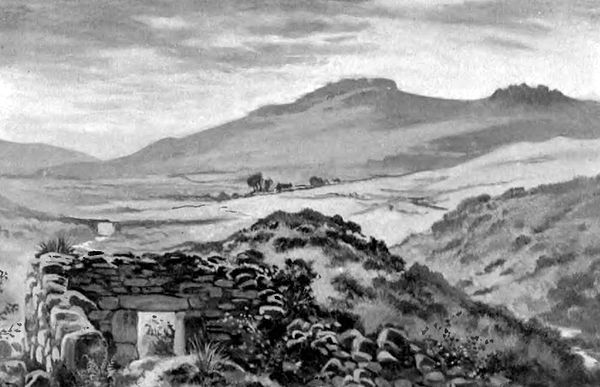

Blowing-house under Black Tor

Above this the stream has been turned about and

Tin-Workings, Nillacome.

its bed torn up, and rubble heaped in huge piles. Not only so, but the hillslope to the south is marked as with confluent smallpox, the result of the gropings of miners after tin. They followed up every trickle from the side and dug costeening, or shoding, pits everywhere in search of metal.

The upper waters of the Webburn have in like manner been explored, and some idea of the extent to which the moor was lacerated by the miners may be obtained from the Warren Inn on the road from Post Bridge to Moreton, looking east, when the slopes of Headland Warren and Challacombe will be seen seamed deeply.

The remains of the tinners have not been subjected to as full an exploration as they merit, but certain results have nevertheless been reached. One thing is abundantly clear, that all the tin-streaming was done subsequently to the time when men occupied the hut circles. The population living in them knew nothing of tin.

Diodorus Siculus, who wrote B.C. 8, says that the dwellers at Belerium, a cape of Britain, mined and smelted tin. "After beating it up into knucklebone shapes they carry it to a certain island lying off Britain, named Ictis, for at ebb tides, the space between drying up, they carry the tin in waggons thither . . . and thence the merchants buy it from the inhabitants and carry it over to Gaul, and lastly, travelling by land through Gaul about thirty days, they bring down the loads on horses to the mouth of the Rhine."

There can exist little doubt that Ictis is the same as Vectis, the Isle of Wight. It is held that anciently the island was connected with the mainland. The Roman station and harbour was at Brading. The early workers first pounded the ore with stone crushers, and such have been found. They then fanned it in the wind, which carried off the fine light dust, and left the metal on the shovels on which they tossed the ore and grit into the air. Beside some of the workings heaps of this dust have been detected. The washing of the ore came later. When sufficient had been collected, long troughs were sunk in the "calm," or native clay, and these were filled with charcoal; then the tin ore was laid on this charcoal, and either more of this latter was heaped above, or else peat was piled

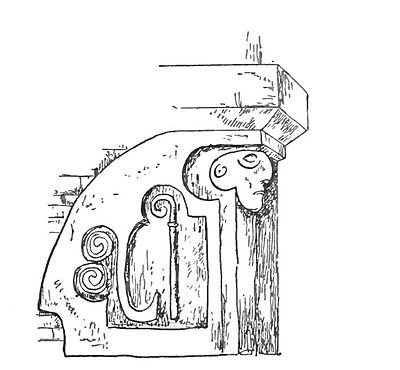

Mortar-stone, Okeford.

up, with layers of ore. Finally the whole was kindled. No bellows were used, but a draught through the channel kept the whole glowing, and the metal ran through the fire into the bottom of the hollow, or ran out at the end, as this rude furnace was constructed on an incline.

In Staffordshire, at Kinver, and in the neighbourhood of Stourbridge, in Worcestershire, I have seen banks and hedges made up of what are locally called burrs. These consist of masses of sand and iron slag, two feet in diameter, round, and concave on one side, convex on the other. These burrs were formed in the primitive manufacture of iron, which much resembled that of tin. Andrew Yarranton, in England's Improvement by Sea and Land, 1698, says that he saw dug up near the walls of Worcester the hearth of an old Roman iron-furnace.

"It was an open hearth upon which was placed alternately charcoal and ironstone, to which fire being applied; it was urged by men treading upon bellows. The operation was very slow and imperfect. Unless the ore was very rich, not more than one hundredweight of iron could be extracted in a day. The ironstone did not melt, but was found at the bottom of the hearth in a large lump or bloom, which was afterwards taken out and beaten under massive hammers previous to its being worked into the required shape or form."

The burrs found are the sand and iron mixed that encased the bloom, which was taken out by pincers and worked on the anvil. The scoria that encased the bloom was thrown aside, and yet contains more than one-half of iron. The iron reduced in this simple manner never ran, but it became soft like dough, and could be removed and beaten into shape.

The method of dealing with the tin was similar, only that in this latter case the metal flowed. That foot bellows were employed before the system of working bellows, and producing a continuous blast by means of a water-wheel, is most probable. The foot bellows are known to most primitive people, but in Agricola's illustration of the smelting of tin

Slag-pounding Hollows, Gobbetts.

none are shown. On the contrary, Æolus is represented in the corner as blowing a natural blast.

The book of Agricola, published in 1556, shows that this primitive method was still in practice so late as the middle of the sixteenth century.

But this clumsy method could not be long practised on Dartmoor, where fuel—except peat—was scarce; and it gave way to a furnace of better construction, where the receiver was circular, and a draught-hole was at the bottom. One of these has

Smelting Ore. (After Agricola.)

been dug out and carefully examined at Deep Swincombe.

Plan of Blowing-house, Deep Swincombe.

At the extremity furthest from the door was a cache in the thickness of the wall, formed something like a kistvaen, as a place in which to store the metal and tools. The whole structure was banked up with rubble and turf.

Outside to the south still lies a mould-stone, a slab of elvan, in which the mould had been cut, measuring 26 inches long by 12 inches at one end and 15 at the other, and 5 inches deep.

That this is the earliest tin-furnace yet discovered on Dartmoor admits of no doubt. The curious mould-stone is quite different in shape from any others found on the moor. No mortar-stones were discovered, and this also is a token of antiquity.

The earliest smelting arrangements must have been very crude, and much tin was left in the slag. Until recently the Malays threw away their slags, which contained as much as 40 per cent of tin. As there have been no mortar-stones found at Deep Swincombe, it is to be presumed that the tinners disregarded their slags. These have not, moreover, been found. The reason was this—the sets had been reworked at a later time by the tinners at Gobbetts, further down the river. These later men had stone

Tin-mould, Deep Swincombe.

mortars and a crazing mill, and finding these rich slags, removed them, pounded them up in the hollowed mortar-stones, that may be seen in situ at Gobbetts, and resmelted them. Deep Swincombe has all the appearance of having been much pulled about by tinners since the first furnace was erected.

The tin running out of the furnace was allowed to flow into holes in the ground, and thence was ladled whilst in a molten condition and poured into the moulds.

Mr. Gowland has given a most interesting account of the manner in which the metals are extracted from their ores in Japan.[1] This shows how that the primitive methods are still in practice there. He says:—

"Although tin ore is found and worked in Japan in several localities, there is but one ancient mine in the country. It is situated in Taniyama, in the province of Satsuma. The excavations of the old miners here are of a most extensive character, the hillsides in places being literally honeycombed by their burrows, indicating the production in past times of large quantities of the metal. No remains, however, have been found to give any clue to the date of the earliest workings. But whatever may have been their date, the processes and appliances of the early smelters could not have been more primitive than those I found in use when I visited the mines in 1883.

"The ore was roughly broken up by hammers on stone anvils, then reduced to a coarse powder with the pounders used for decorticating rice, the mortars being large blocks of stone with roughly hollowed cavities.

"It was finally ground in stone querns, and washed by women in a stream to remove the earthy matter and foreign minerals with which it was contaminated. The furnace in which the ore was smelted is exactly the same as that used for copper ores, excepting that it is somewhat less in diameter. The ore was charged into it wet, in alternate layers with charcoal, and the process was conducted in precisely the same way as in smelting oxidised copper ores. The tin obtained was laded out of the furnace into moulds of clay."

The furnace employed for copper is also described by Mr. Gowland:—

"An excavation, measuring about 4 feet long, 4 feet wide, and 2 feet deep, is made, and this is filled with dry clay carefully beaten down. In the centre of this bed of clay a shallow, conical-shaped hole is scooped out. The hole is

Smelting Tin in Japan.

then lined with a layer, about three inches thick, of damp clay mixed with charcoal, and the furnace is complete.

"It has no apertures either for the injection of the blast or for tapping out the metal. A blast of air is supplied to it generally from two bellows, placed behind a wall of wattle well coated with clay, by which they and the men working them are protected from the heat. The blast is led from each bellows by a bamboo tube, terminating in a very long nozzle of clay, which rests on the edge of the furnace cavity."

At Deep Swincombe no bellows were used; the draught probably came in through the hole behind the furnace.

But in the reign of Queen Elizabeth a great revolution in the smelting of tin was wrought by the introduction of German workmen and their improved methods. They brought in the water-wheel. The ruins that are found in such abundance of "blowing-houses," as they are called—one at the least beside every considerable stream—belong, for the most part, to the Elizabethan period. They have their "leats" for carrying water to them, and their pits for tiny wheels that worked the bellows.

The situation of these smelting-houses may be found usually by the mould-stones that lie near them. There is one below the slide or fall of the Yealm, with its moulds in and by it, and another just above the fall. There is one near the megalithic remains at Drizzlecombe, also with its mould-stones. But it is unnecessary to particularise when they are so numerous. I will, however, quote Mr. R. Burnard's description of two in the Walkham valley as typical:

"The first is about 250 yards above Merrivale Bridge, on the left bank of the river. One jamb is erect, and, like most of the doorways of Dartmoor blowing-houses, was low, and to be entered necessitated an almost all-fours posture. Very little of the walls is standing, but what remains is composed of large moor-stones, dry laid. Near the entrance is a stone, 3 feet long and 2½ feet wide, containing a mould, which at the top is 18 inches long, 13 inches wide, and 6 inches deep. The sides are bevelled, so that the bottom length is 12½ inches, with a width of 7 inches at one end and 8 inches at the other. One end of the mould has a narrow gutter leading from the top to halfway down the mould. This was probably used for the insertion of a piece of iron prior to the metal being run in, thus permitting the easy withdrawal of the block of tin when cool from the mould. This stone also contains a small bevelled ingot or sample mould, 4 inches long, 2 inches wide, and 1¼ inches deep.

"A water-wheel probably stood in the eastern recess of the house, for there is a covered drain leading from here right under the house and out at the western end, where the water was discharged into the river. Traces of the leat which supplied the motive power to this wheel may also be seen.

"What appear to be the remains of the furnace, consisting of massive stones placed vertically, and inclosing a small rectangular space, are plainly visible. In this place, lying askew, as if it had been thrown out of position, is a large stone containing a long, shallow cavity, which may have been the bottom of the furnace or 'float,' i.e. the cavity in which the molten tin collected before being ladled into the mould.

"This ruin lies at the nether end of deep, open cuttings, which start from near Rundlestone Corner, and are continued right down to the Walkham.

"About 1,000 yards up stream is the ruin of the other blowing-house, with remains of a wheel-pit and a leat. There is also a stone containing a mould 16 inches long at the top, 11 inches wide, and 6 inches deep. It is bevelled, so that the bottom length is 12½ inches, with a width of 8 inches. Like the mould-stone in the ruin below, it contains a sample ingot mould 3½ inches long, 3 inches wide, and 2 inches deep. The remains in these ruins are very similar to each other, and these blow-houses were probably smelting during the same period, indicating that a considerable quantity of tin was raised in their neighbourhood."[2]

Anciently, before the introduction of the wheel, the smelting-place above all others was at King's Oven, or Furnum Regis, near the Warren Inn, between Post Bridge and Moreton. It is mentioned in the Perambulation of Dartmoor, made in 1240. It consists of a circular inclosure of about seventy-two yards in diameter, forming a pound, with the remains of a quadrangular building in it. The furnace itself was destroyed some years ago. When the inclosure was made it was carried to a cairn that was in part demolished, to serve to form the bank of the pound. This cairn was ringed about with upright stones, and contained a kistvaen. The latter was rifled, and most of the stones removed to form the walls; but a few of the inclosing uprights were not meddled with, and between two was found firmly wedged a beautiful flint scraper.

As the drift tin was exhausted, and the slag of the earlier miners was used up, it became necessary to run adits for tin, and work the veins. These adits remain in several places, and where they have been opened have yielded up iron bars and picks. But these are not more ancient than mediæval times, probably late in them. That gold was found in the granite rubble of the stream-beds is likely. A model of a gold-washing apparatus was found on the moor a few years ago. It was made of zinc.

According to an old Irish historical narrative, a bard was wont to carry a wand of "white bronze" or tin, and his shoes were also tin-plated.[3] One wonders whether at any time a bard thus shod and with his rod of office strode over Dartmoor and chanted historic ballads there!

For such as would care to see these dry bones of antiquarian research into the past of tin-streamers clothed with flesh, I must refer them to my novel of Guavas the Tinner, in which I have described the mode of life of the metal-seekers on the moor in the time of Elizabeth.