IVYBRIDGE

The moors on the south not bold—South Brent—Destruction of the screen—The Avon—Zeal Plains crowded with prehistoric remains—The Abbots' Way—Huntingdon's Cross—Petre's Cross—Hobajohn's Cross—Stone row—Remains upon Erme Plains—The Staldon stone row—Other rows—Beehive huts—Harford church—Hall—The Duchess of Kingston—The Yealm valley—Blowing-houses—Long wall—Hawns and Dendles—The tripper and ferns—Wisdome—Slade—Fardell—The Fardell Stone.

THIS not very interesting spot may be chosen as a centre whence the Avon, Erme, and Yealm river valleys may be explored. The distances are considerable, but the railway facilitates reaching starting-points—South Brent for the Avon, and Cornwood for the Yealm. It is advisable to ascend one river, cross a ridge, and descend another river.

The moors on this, the south, side are by no means so bold as are those on the other sides, but the valleys are hardly to be surpassed for beauty; and they give access to very remarkable groups of antiquities, the distance to some of which beyond inclosed land, and the absence of roads on this part of the moor has saved these latter from destruction.

In Ivybridge itself there is absolutely nothing worth seeing, but the churches of Ugborough and Ermington richly deserve a visit; and there are some old manor houses, as Fardell, Fillham, Slade, and Fowelscombe, that may be seen with interest. We will begin with the valley of the Avon.

South Brent is dominated by Brent Hill, that was formerly crowned with a chapel dedicated to S. Michael. The parish church, a foundation of S. Petrock, possessed a fine carved oak screen. The church has, however, been taken in hand by that iconoclast the "restorer," who has left it empty, swept and garnished—a thing of nakedness and a woe for ever. The screen—the one glory of the church—was cast forth into the graveyard, and there allowed to rot.

The Avon foams down from the moor through a contracted throat, affording scenes of great beauty in its ravine. It receives the Glazebrook some way below South Brent, and the Bala about the same distance above it.

The river has to be ascended for two miles and a half before Shipley Bridge is reached, and then the moor is in front of one, with Zeal Plains spread out, strewn with prehistoric settlements that have not as yet been properly investigated.

The Abbots' Way, a track from Buckfast to Tavistock, crosses the Avon at Huntingdon's Cross, a rude unchamfered stone four feet and a half high. It stands immediately within the forest bounds. The moors already traversed are the commons of Brent and Dean. The cross is romantically situated in a rocky basin, the rising ground about it covered with patches of heather, with here and there a granite boulder protruding through the turf.

"All around is still and silent, save the low murmuring of the waters as they run over their pebbly bed. The only signs of life are the furry inhabitants of the warren, and, perchance, a herd of Dartmoor ponies, wild as the country over which they roam, and a few sheep or cattle grazing on the slopes. The cross is surrounded by rushes, and a dilapidated—wall the warren enclosure—runs near it."[1]

The Abbots' Way may here be distinctly seen ascending the left bank of the Avon.

On Quick Beam Hill, over which the Abbots' Way climbs to reach the valley of the Erme, is another cross, concerning which something must be said, as it shows that not only educated and intelligent architects are iconoclasts, but also illiterate and stupid workmen.

There is a cairn that bears the name of Whitaburrow, and till the year 1847, erect on it in the centre stood an old grey moorstone cross. In that year a company was formed to extract naphtha from the peat, and its works were established near Shipley Bridge, to which the peat was conveyed from this spot in tram-waggons.

There being no place of shelter near, the labourers erected a house on the summit of the cairn, which measures one hundred and ninety feet in circumference, and requiring a large stone as a support for their chimney-breast, they knocked off the arms of the cross and employed the shaft for that purpose. The house has disappeared with the exception of the foundations and about three feet in height of walling, but the poor old maimed shaft stands there aloft, just as the poor old maimed church of South Brent stands on the river far below. Each has lost that which made it significant and beautiful, each mutilated by the stupidity of man.

The cross takes its name from Sir William Petre of Tor Brian, who possessed certain rights over Brent Moor. He was Secretary of State in four reigns—those of Henry VIII., Edward VI., Mary, and Elizabeth—and seems to have conformed to whichever religion was favoured by the Sovereign, like the Vicar of Bray. He died in 1571, and was the ancestor of the present Lord Petre.

On Ugborough Moor, that adjoins, is a third cross, called that of Hobajohn, which is planted, singularly enough, in the midst of a stone row. This row starts on Butterdon Hill, above Ivybridge, and passes within a short distance of Sharp Tor. I have not seen it, but learn that it, like most other stone rows, starts from a cairn inclosed within upright stones. It must, if really a stone row, be something like three miles in length. The cross has also been mutilated, and lies prostrate.

A fourth cross, Spurle's or Pearl's Cross, on Ugborough Moor, has lost its shaft.

The Abbots' Way from Avon valley leads to the Erme valley, where Redlake enters it at a very interesting point. Here, at the junction of this feeder, is a well-preserved blowing-house, with its wheel-pit and with its tin-moulds lying in the ruins.

The whole of Erme Plains and the valley for three miles down is simply crowded with hut circles, pounds, and other remains. On the height above, Staldon Moor, is a stone row of really astounding length, of which something has been already said. It starts at the south end from a large circle, which formerly inclosed a cairn, and stretches away to the north, over hill and down dale, for two miles and a quarter, and terminates in a kistvaen. The stones are not large, but the row is fairly intact.

Due south of this, on the south side of the highest point of Stall Moor, Staldon Barrow, are two more stone rows, almost, but not quite, in a line. In the neighbourhood are many cairns and kistvaens. The stones here are larger. Taken together the rows run over 1,400 feet. They can be seen from Cornwood Station when the light is favourable.

Again another row on Burford Down, a continuation of the same moor, starts from a circle containing a kistvaen near Tristis Rock, and stretches away north to a wall and across an inclosed field, but here it has been sadly pillaged for the construction of the wall. It still runs 1,500 feet. The Erme valley has been much worked by streamers, and some of the mining operations have been carried on at a comparatively recent period.

By the side of a little lateral gully on the right hand in descending the river is a beehive hut among the streamers' mounds; it is quite intact, and shelter may be taken in it from a passing storm. It is, however, not prehistoric, but is a miners' cache.

Another, also perfect, is a little further down, on the other side of the river before reaching Piles Wood.

Harford church, another foundation of S. Petrock, stands high. It contains nothing of interest except an altar tomb with brasses upon it, in memory of Thomas Williams, Speaker of the House of Commons, of the family of that name formerly resident at Stowford, in the parish. And in the second place, a monument to John and Agnes Prideaux, the parents of John Prideaux, Bishop of Worcester. This was set up by the latter in 1639.

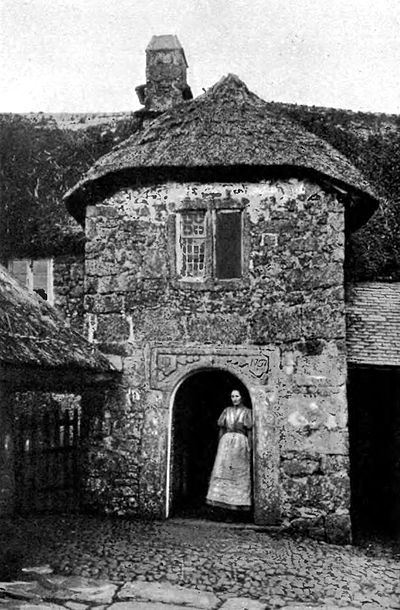

Hall, not far from the church, was for some time the residence of the notorious Elizabeth Chudleigh, Duchess of Kingston, who was tried and condemned for bigamy. It was a hard case. She was born in 1726, and was the daughter of Colonel Thomas Chudleigh, who died when Elizabeth was quite a child. In 1744, when she was aged only eighteen, she visited her maternal aunt, Anne Hanmer, at Lainston, near Winchester, met at the Winchester Races Lieutenant Hervey, second son of Lord Hervey, and grandson of the Earl of Bristol, who was then aged twenty. He was invited to Lainston, and one night in a foolish frolic, at eleven o'clock, with the connivance, if not at the instigation, of Mrs. Hanmer, Elizabeth was married to Lieutenant Hervey by the rector in the little roofless ruin of a church. No registers were signed, and the bridegroom left in two days to rejoin his ship, and sailed for the West Indies.

She never after that received Lieutenant Hervey as her husband, and he instituted a suit in the Consistory Court of the Bishop of London for the jactitation of the marriage, and sentence was given in 1769 declaring that the marriage form gone through in 1744 was null and void. On the strength of this Elizabeth married the Duke of Kingston, March 8, 1769.

No attempt was made during the lifetime of the Duke to dispute the legality of the union; neither he nor Elizabeth had the least doubt that the former marriage had been legally dissolved. But when the Duke left all his great fortune to Elizabeth, then his nephews were furious, and raked up against her the charge of bigamy, on the grounds that the sentence of the Consistory Court was invalid. She was tried in Westminster Hall before her peers in 1776, and the trial lasted five days.

The penalty for bigamy was death, but she could escape this sentence by claiming the benefit of a statute of William and Mary, which commuted death to branding in the hand and imprisonment. The peers found her guilty, but she escaped punishment by flying to the Continent, where she died in 1788.[2]

Harford Hall, where she resided, has about it no architectural features; it never can have been other than a small mansion, and is now a mere farmhouse. The trees around it alone indicate that it was at one time a gentleman's seat.

If now we strike across Stall Moor to the Yealm we come on Yealm Steps, where the river falls over a mass of granite débris. Here are two blowing-houses, one above the steps and the other below. The lower house on the eastern side of the stream is a mere heap of ruins with, however, the door-jamb standing and facing the north.[3] No wheel-pit is visible, but there are traces of a watercourse at a high level to the north-east of the hut. Near the entrance is a stone with one perfect mould in it, and another imperfect. A second mould-stone is lying near an angle in the eastern wall of the house. It has in it two moulds adjoining each other—one at a lower level than the other, and connected by a channel. The high-level cavity is 15 inches long, 8 inches wide, and 3 inches deep. At one end is a groove one inch deep, perpendicular, and running down the side of the mould three inches; that is, from top to bottom.

The low-level mould is 17 inches long, 12 inches wide, and 5 inches deep. These cavities have been used for the purification of tin, for the molten metal mixed with furnace impurities poured in on the high-level hollow would flow in a purer condition into the low-level mould.

This blowing-house has been excavated, somewhat superficially, but nothing was found in it to give token of the period to which it belonged. About a quarter of a mile further up the river, but on the western bank, is another ruin. The doorway, which is very imperfect, is on the eastern side. One mould-stone remains, containing a mould 17 inches long, 12 inches wide, and from 4 to 5 inches deep.

The whole slope of Stall Moor towards the south is strewn with hut circles, and between the Yealm and Broadall Lake is a pound containing several. On the further side of the stream is another pound, at which begins a singular wall that extends for over three miles as far as the Plym at Trowlesworthy Warren. For what purpose this wall was erected—whether as a boundary, or whether for defence—cannot be determined. It is in connection with several pounds and clusters of hut circles.

In the valley of Hawns and Dendles is a pretty cascade, a great haunt of the tripper, who ravages the Yealm valley and tears up and carries off the ferns and roots of wild flowers.

A few instances of the habits of the tripper may not seem amiss, as exhibited in the Yealm valley.

Blachford was the residence of the late Lord Blachford, the friend of Gladstone.

One day my lady saw a woman—a tripper—in front of the house, where there is a rockery, tearing up ferns. Lady Blachford rushed forth to interfere.

"Oh!" said the tripper, "I only did it so as to get a sight of Lord Blachford. I thought if I executed some mischief I might draw him forth."

A peculiarly fine rhododendron grew in front of the vicarage. It attracted the tripper by its beautiful masses of flower. One evening an individual of this not uncommon species proceeded to tear it up, assisted by trowel and knife; and finally having hacked through the roots, carried it off; but finding the load burdensome at the first hill, threw it away.

A gentleman residing further down the valley was cultivating a rare flowering shrub. After seven years it put forth its tassels of bloom. He tarried a day or two before gathering the blossoms till they were fully out. His wife was an invalid, and he purposed showing them to her when in their full perfection. But before he carried his purpose into execution, he went to Cornwood Station to meet a friend, when he perceived a "lady" on the platform with her hands full of the flowers. He approached her and civilly inquired where she had obtained the beautiful bunches.

"Oh! they were growing in Mr. P.'s ground, so I went in and gathered them. I know Mr. P. well, and I am convinced he would not object."

"You have the advantage of me, madam. I am Mr. P. But to a lady, as to a Christian, all things are lawful, though all things may not be expedient."

A friend threw open his grounds to a great party of school teachers and their scholars. The neighbourhood had been denuded of the Osmunda regalis by the tripper, but the beautiful fern had a sanctuary in his preserves. However, the visitors dug up, tore away, and destroyed his plants wholesale, and returned to town burdened with the wreckage. The Osmunda is a slow grower, and takes many years to reach maturity.

So much for the tripper. I do not in the least suppose any of this race will see more of my book than the outside. But I write this for the intelligent visitor, to warn him against Hawns and Dendles on Plymouth early closing day (Wednesday) in summer.

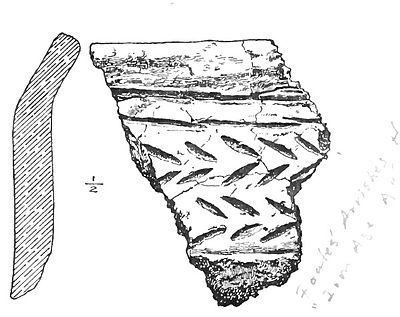

Wisdome is the ancestral house of the Rogers family, of which the late Lord Blachford was the representative. It is a modest, picturesque old moorland mansion of a small gentle family. Slade, on the other hand, must have been a house of consequence; it still possesses a noble hall, with richly carved oak wainscotting. Steart has handsome carved armorial gates; and Fardell is remarkable as a home of the Raleigh family, and had its licensed chapel. The grandfather of the navigator lived at Fardell, and Sir Walter himself was probably there much in his early days. Here was found an ogham inscription on a stone, now in the British Museum, which shows that the Irish had conquered and colonised Devon as far south as Cornwood. Other oghams have been found at Tavistock, and at Lewannick, near Launceston.

According to local belief, the stone indicated where treasure was hid; and a jingle was current in the neighbourhood:—

"Between this stone and Fardell Hall

Lies as much money as the devil can haul."

Lies as much money as the devil can haul."

The stone bore the inscription, "Fanonii Macquisini" on one side, and "Sapanni" on the other. The "Mac" in the name is conclusively Irish, as also the oghams.